A Consilient Test of Philology, Ecology, and Sundaland Plausibility

Related articles:

- Decoding Plato’s Atlantis: A Consilience-Based Reconstruction of the Lost Capital

- Critias 115a–b & 118e: The Provisioning Complex of Staple and Companion

- Inside the “Mouth”: Rereading Plato’s Pillars of Heracles as a Navigational Gate

- Coconuts

- Decoding Signs of the Past: A Semiotic and Linguistic Framework for Historical Reconstruction

A research by Dhani Irwanto, 21 September 2025

Abstract

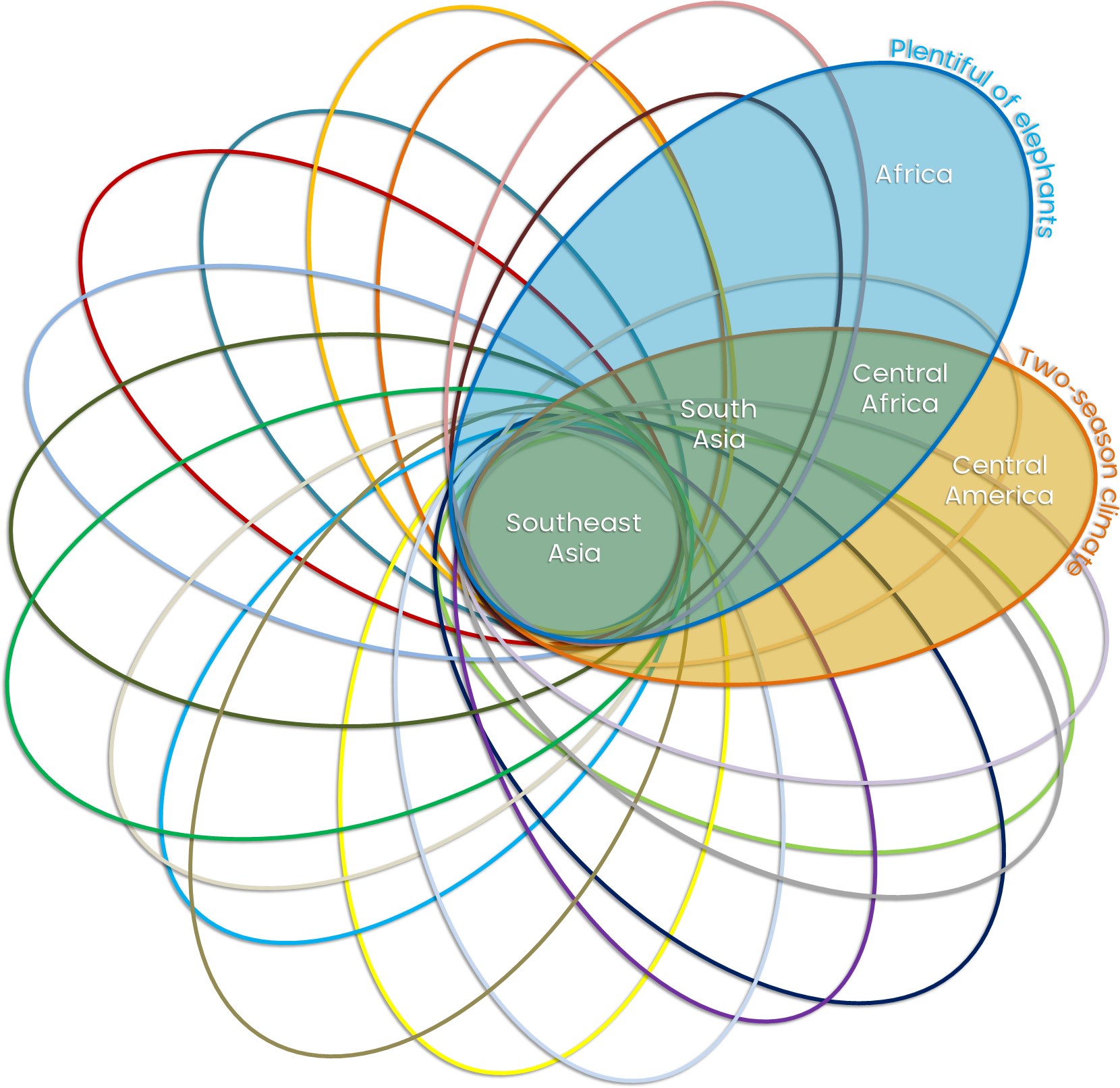

This study revisits Critias 115a–b, where Plato records the Egyptian priest’s description of the fruits of Atlantis, emphasizing both extraordinary size and a tetradic utility: hard rind, drink, food, and oil. These descriptions have long puzzled commentators, as no Mediterranean species fulfills all four functions. By applying a consilience framework integrating semiotics, philology, linguistics, archaeobotany, ecology, and cultural history, this article argues that the coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) uniquely satisfies the textual criteria. The tetrad is interpreted as a set of context clues deliberately supplied to Solon for a product unfamiliar to Classical Greece. Order-1 analysis establishes the denotative baseline; Order-2 clarifies pragmatic intent and audience reception; Order-3 integrates ecological suitability, genetic timelines, Austronesian cultural continuities, and spatial models of Sundaland. Counter-fruit testing eliminates alternative candidates, while explicit falsifiability criteria ensure that the hypothesis remains open to disproof. In integration with other puzzle pieces—elephants, rice and legumes, reef shoals, and the East-Mouth spatial model—the coconut emerges as a decisive marker of Sundaland’s ecological and cultural plausibility as Atlantis’ setting. The result is not only a refined reading of Plato’s text but also a testable historical claim that bridges myth, ecology, and prehistory.

Keywords: Plato; Critias 115b; coconut; Cocos nucifera; tetrad; context clues; Sundaland; Atlantis; semiotics; philology; consilience; Austronesian; pre-Columbian contacts.

1. Problem Definition

1.1 Aim & Scope

The central aim of this article is to evaluate the coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) as a potential puzzle piece in the reconstruction of Atlantis when situated within the Sundaland framework. This evaluation requires more than a botanical description; it calls for a multidisciplinary approach that spans philology, semiotics, linguistics, archaeobotany, and cultural anthropology. The scope of the inquiry is not confined to identifying a fruit that fits Plato’s description but extends to assessing how such a fruit could function as a communicative bridge between the Egyptian priest and Solon, and by extension, between the ancient world and the modern researcher. By refining both textual anchors and contextual interpretations, this section establishes why the coconut is worth considering and how its analysis contributes to the broader Sundaland–Atlantis hypothesis.

1.2 Textual Anchors and Contextual Hypothesis

Plato’s dialogues contain a handful of striking agricultural references, two of which stand out as possible allusions to coconut. The first appears in Critias 115a, where the land of Atlantis is said to bear ‘καρπὸς θαυμαστὸν τὸ μέγεθος’ (karpòs thaumastòn tò mégethos), literally ‘fruit wondrous in size.’ The second, more elaborate passage is found in Critias 115b:

“… καὶ τοὺς καρποὺς τοὺς σκληροφόρους, πόματα καὶ ἐδωδὰς καὶ ἀλείμματα παρέχοντας …”

Transliteration: “… kai toùs karpoùs toùs sklērophórous, pómata kaì edodàs kaì aleímmata parékhontas …”

Literal translation: “… and the fruits having a hard rind, providing drinks and meats and ointments …”

Taken together, these two textual anchors yield a description of both extraordinary size and fourfold utility. The latter is particularly significant, as it points not merely to a generic fruit but to a tetrad of functions: (1) husk or shell (σκληροφόρους, sklērophórous), (2) liquid drink (πόματα, pómata), (3) edible flesh (ἐδωδάς, edodàs), and (4) oil or ointment (ἀλείμματα, aleímmata). This tetradic pattern maps directly onto the coconut’s properties and surpasses the descriptive adequacy of any Mediterranean species. The Egyptian priest’s choice to describe rather than name the fruit suggests an intentional strategy of supplying Solon with context clues for something outside Greek experience.

1.3 Key Lexemes

Several Greek words in these passages are decisive for interpretation:

- καρπός (karpós) — generic term for fruit or produce, without species specificity.

- θαυμαστόν (thaumastón) — marvelous, wondrous, denoting both admiration and unfamiliarity.

- μέγεθος (mégethos) — magnitude, size, scale beyond the ordinary.

- σκληροφόρους (sklērophórous) — literally ‘hard-rind-bearing,’ an unusual descriptor in agricultural contexts.

- πόματα (pómata) — drinks, liquids suitable for consumption.

- ἐδωδάς (edodàs) — foods or meats, highlighting nutritive content.

- ἀλείμματα (aleímmata) — ointments or oils, typically derived from plants.

This lexical constellation indicates not a poetic flourish but a functional inventory. The tetrad is too specific to be incidental: it points to a practical knowledge of a foreign plant whose properties were being translated into Greek conceptual categories.

1.4 Context-Clue Hypothesis and Unfamiliarity Claim

The deliberate use of a functional tetrad rather than a name implies a communicative act designed to overcome unfamiliarity. The Egyptian priest, aware that Solon would not recognize the fruit by name, supplied its uses as context clues. These clues were pedagogical in nature: they bridged the cultural gap between an Egyptian knowledge of exotic products and a Greek listener unacquainted with them. For Plato’s audience, however, the effect was one of marvel and exoticism, reinforcing Atlantis as a land of abundance and strangeness. This unfamiliarity claim is central to understanding why the description survives not as a loanword but as a tetradic inventory of functions.

1.5 Timeline Policy

A methodological safeguard is required when handling these passages: Solon’s reception of the priest’s words may reflect either contemporary Egyptian knowledge of coconut through Indian Ocean trade or inherited memory of earlier exchanges connected to Sundaland. The present-tense verbs used in Critias (ἐξέφερε, exéphére, ‘it bore forth’) suggest immediacy, but transmission effects may blur temporal boundaries. For analytical purposes, this study treats the description as a preserved fossil of real knowledge, whether current in Solon’s time or remembered from deeper antiquity.

1.6 Research Questions (What Must Be Solved)

From these anchors, lexemes, and context clues, several guiding research questions emerge:

- Can the tetradic description in Critias 115b be convincingly mapped onto the coconut’s properties?

- Does the use of context clues confirm that the priest was describing an unfamiliar yet real product rather than a metaphorical abundance?

- How does the coconut integrate with other puzzle pieces such as rice, legumes, elephants, and the East-Mouth spatial model?

- What external evidence (archaeobotanical, genetic, linguistic) supports the antiquity and distribution of coconut in the Indo-Pacific?

- What safeguards and falsifiability tests are necessary to ensure the hypothesis remains rigorous and not merely confirmatory?

These questions frame the methodological path forward and clarify why coconut deserves focused analysis within the Atlantis–Sundaland research program.

2. Methods

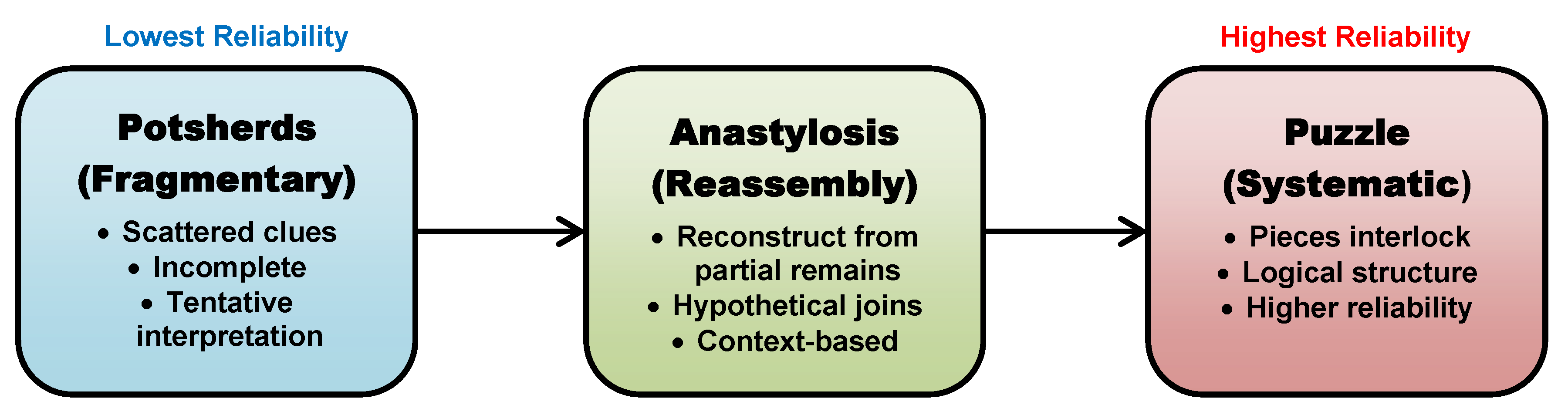

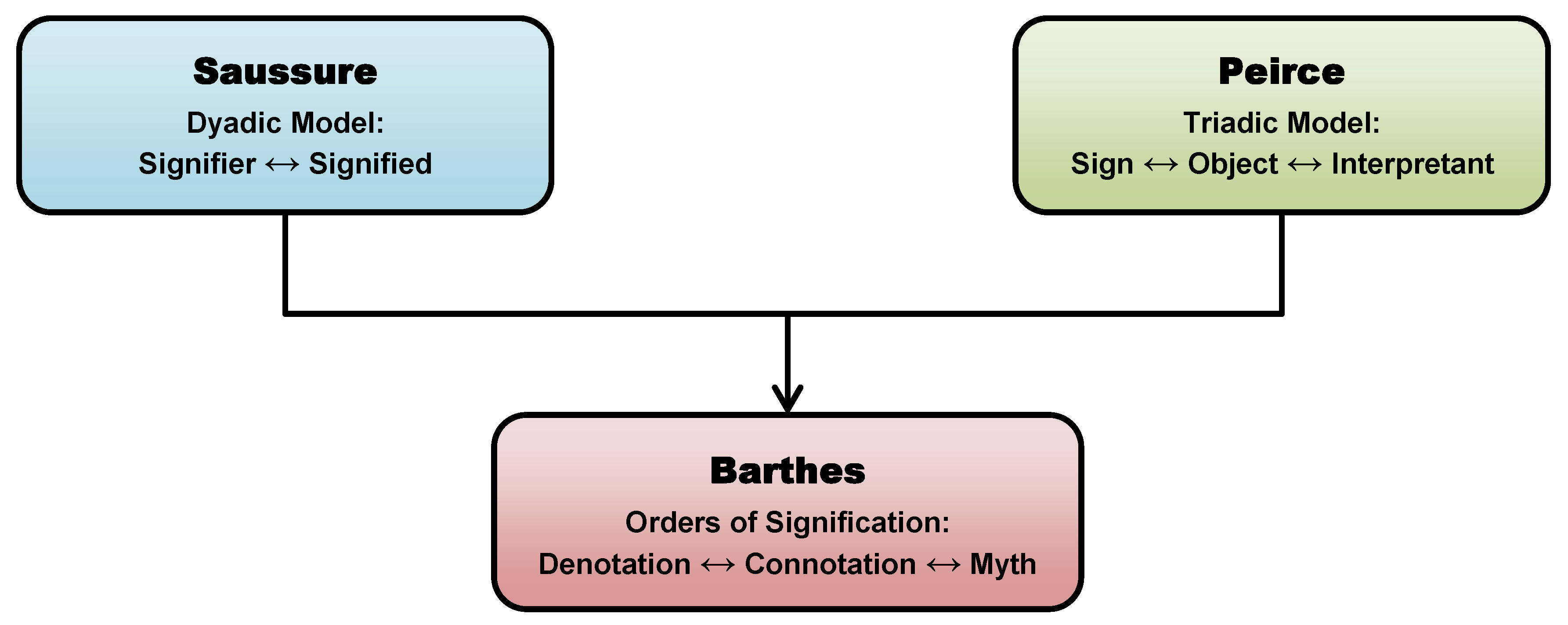

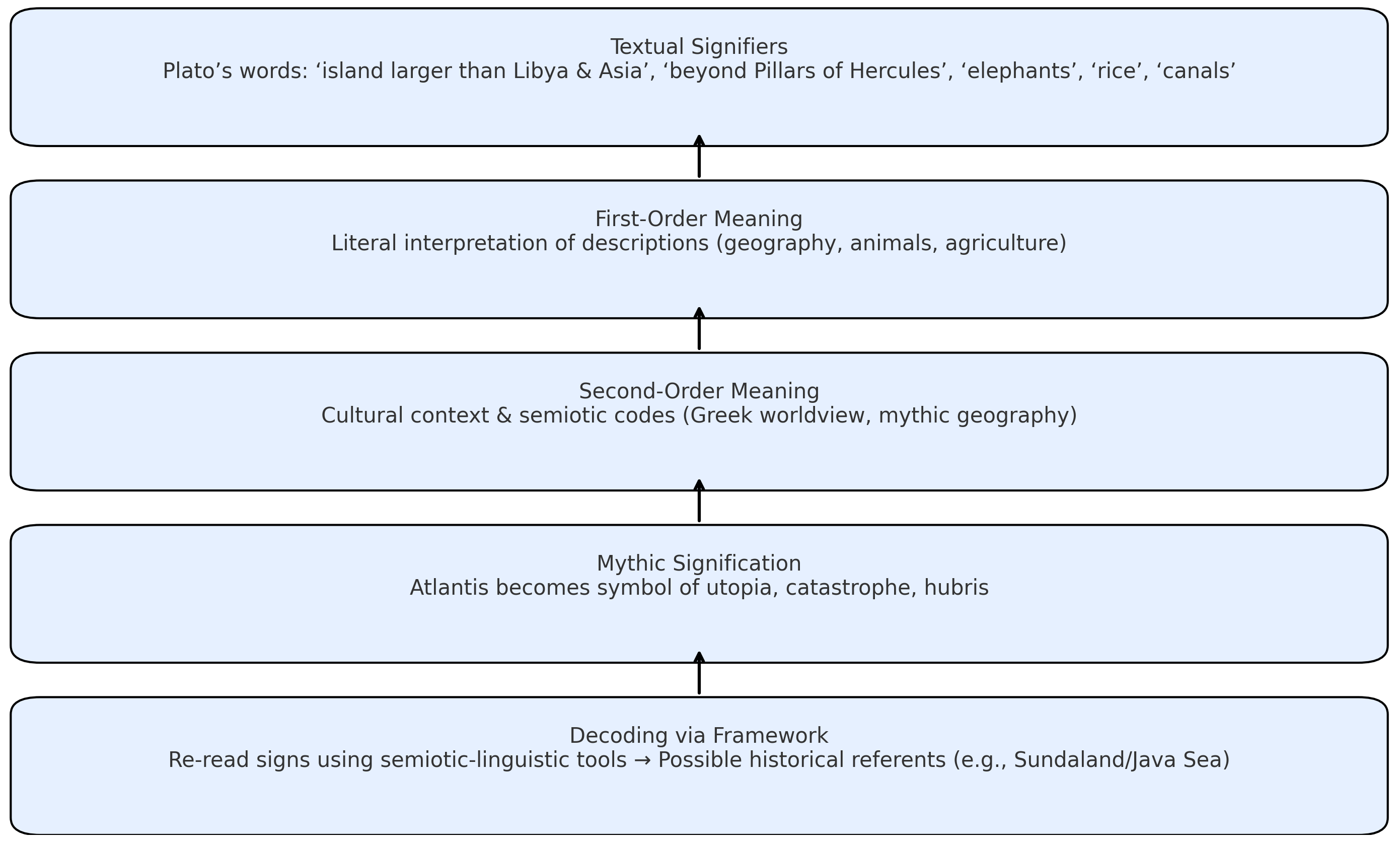

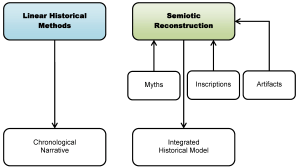

2.1 Semiotics

Semiotics provides the conceptual framework for decoding Plato’s references to agricultural products that were unfamiliar to his audience. The coconut tetrad in Critias 115b—hard rind, drink, food, oil—is especially suited to semiotic analysis because it appears as a deliberate set of signs chosen to communicate across cultural gaps. By using semiotics, we can trace how signs functioned at multiple levels: as literal descriptors, as connotative symbols of exotic abundance, and as mythic markers of Atlantis’ otherness.

- Saussure’s Dyadic Model: The relationship between signifier and signified is destabilized here. The priest uses the general signifier καρπός (karpós, fruit) but supplements it with descriptive functions, since the precise signified—coconut—was unknown in Greek lexicon. This gap is filled by functional descriptors.

- Peirce’s Triadic Model: The interpretant is central. For Solon, the tetrad served as practical context clues to approximate an unfamiliar referent. For Plato’s audience, however, the same tetrad produced the interpretant of exotic marvel, an image of distant abundance.

- Barthes’ Orders of Signification: At the first order (denotation), the tetrad enumerates material uses. At the second order (connotation), it signals strangeness and wealth. At the third order (myth), it naturalizes Atlantis as a land of wondrous fertility beyond Mediterranean norms.

2.2 Linguistics

Linguistic analysis sharpens the reading of Critias 115a–b by focusing on semantics and contextual cues. The choice of words such as σκληροφόρους (sklērophórous, hard-rind-bearing) and ἀλείμματα (aleímmata, ointments) is unusual in classical agricultural registers. These lexemes, when clustered together with πόματα (pómata, drinks) and ἐδωδάς (edodàs, foods), form a tetradic set that describes not a symbolic fruit but a specific utilitarian profile. The priest’s enumeration thus reads as a functional inventory—intelligible through usage rather than through species naming.

2.3 Language Analysis

Language analysis applies structural and pragmatic tools to test whether the tetrad holds under substitution and contextual shifts:

- Syntagmatic Analysis: The sequential ordering (hard rind → drink → food → oil) implies completeness, suggesting that the priest deliberately arranged the functions to convey a full profile.

- Paradigmatic Analysis: Substitution with familiar Mediterranean fruits shows immediate failure. A fig offers sweet flesh but no drink or oil. A pomegranate has arils and juice but no hard rind or oil. The tetrad collapses without coconut.

- Commutation Test: If one function is replaced (e.g., substituting ‘ointment’ with ‘wine’), coherence is lost. The tetrad is fragile and holds only with coconut.

- Pragmatics: The priest chose functional descriptors rather than a name precisely to bridge the gap between his knowledge and Solon’s ignorance. The tetrad thus acted as a teaching tool—a form of cross-cultural pedagogy.

2.4 Philology

Philological examination shows that the tetradic lexemes are authentic and consistent across manuscript traditions. Their combination is unique in Greek literature, where fruits are usually described in terms of sweetness, fertility, or abundance, but rarely through such a fourfold functional inventory. This anomaly strongly suggests that the priest was transmitting real practical knowledge of a foreign plant. In this sense, the tetrad is a philological fossil of cross-cultural knowledge exchange.

2.5 Timeline Discipline

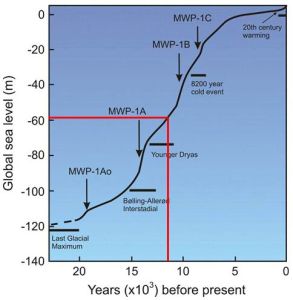

To avoid anachronism, the tetradic description must be tested against the known timeline of coconut domestication and dispersal. Archaeobotanical and genetic studies confirm that coconuts were already widespread in Southeast Asia and had reached the Indian Ocean by the second millennium BCE. This makes it plausible that Egyptians or Phoenicians could have encountered coconut products. The timeline discipline thus permits us to read Critias 115b as reflecting current or remembered reality rather than pure invention.

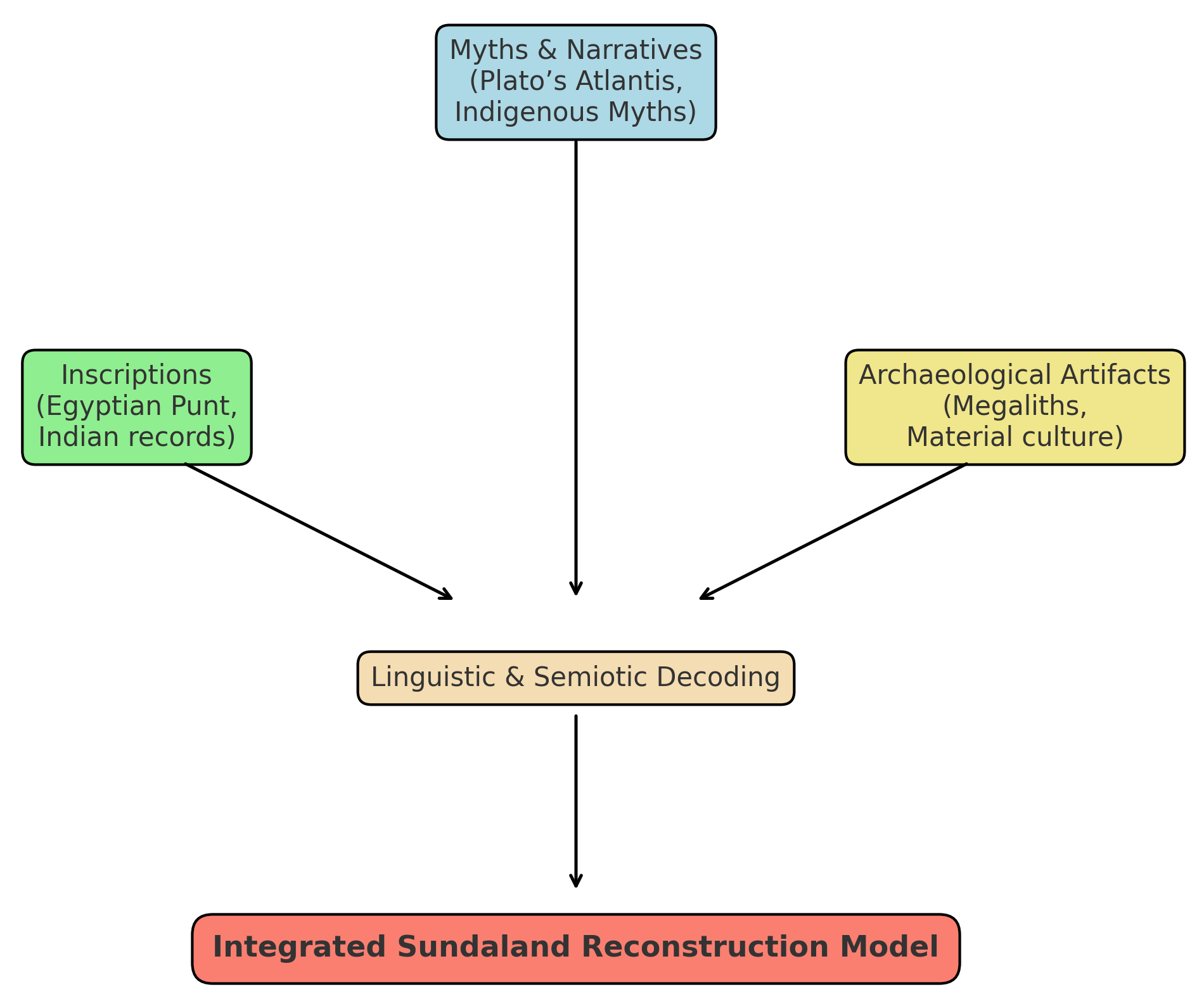

2.6 Order-3 Analysis

At the highest integrative level, Order-3 analysis situates coconut within a puzzle piece catalogue of multiple evidentiary strands relevant to Sundaland Atlantis. The coconut tetrad is tested for consilience across textual, ecological, cultural, and spatial domains.

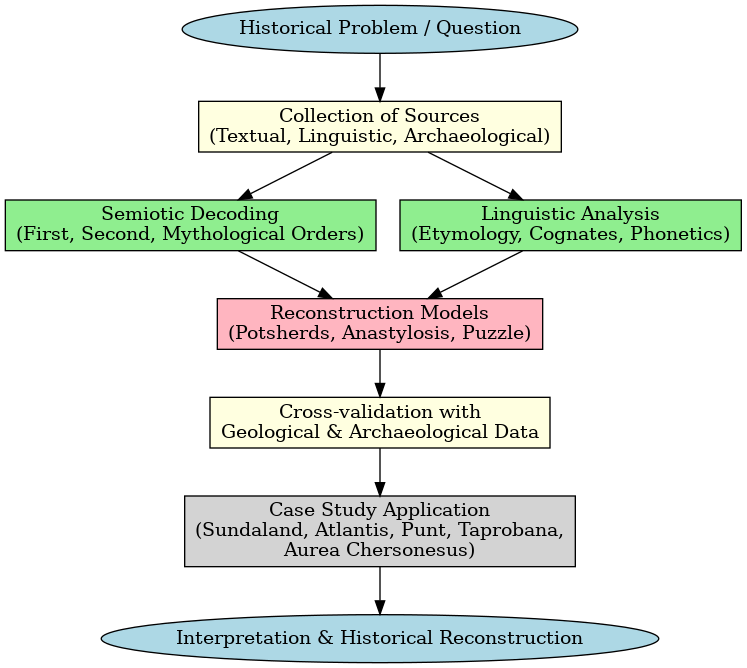

2.6.1 Evidence Classes

The main evidence classes include philological anchors (Critias 115a–b), linguistic features, archaeobotanical and genetic data, ecological and climatic factors, cultural practices, and spatial models. Each contributes independently to the evaluation.

2.6.2 Puzzle Piece Catalogue

The catalogue includes elephants, rice and legumes, coconut origin and distribution, climatic suitability, coconut tradition, East-Mouth spatial model with nautical corridors, ancient trans-oceanic contacts, coral-reef shoal chronology, timeline discipline, legendization in transmission, and toponymic/lexical parallels. Each functions as an independent puzzle piece, with coconut distinguished by its unique tetradic profile.

2.6.3 Consilience Test

Consilience testing is applied by scoring each puzzle piece across independent domains—textual specificity, biogeographic fit, archaeobotanical and genetic data, cultural continuity, spatial plausibility, subsistence coherence, timeline discipline, and transmission robustness. Each criterion is rated on a 0–3 scale (0 = absent; 3 = strong and specific) and weighted according to its diagnostic power. The composite score is calculated by summing the weighted contributions.

This procedure does not presuppose the outcome for any single candidate but establishes a transparent framework by which all puzzle pieces can be evaluated. Later sections apply this method to coconut and alternative fruits, reporting scores and thresholds to distinguish between strong, tentative, and weak support. In this way, the consilience test operates as a methodological bridge between individual lines of evidence and the integrative results.

2.6.4 Counter-Fruit Test

The counter-fruit test introduces systematic comparison by substituting alternative species—such as pomegranate, fig, date palm, breadfruit, calabash, and areca/betel nut—for the tetrad described in Critias 115b. Each candidate is assessed against the four functional criteria (hard rind, drink, food, oil) using the same scoring rubric applied to coconut. The test is designed not to assume failure in advance but to create a transparent comparative framework that challenges the coconut hypothesis. Results of these substitutions are presented in Section 4, where their performance relative to coconut is documented.

2.6.5 Falsifiability

Falsifiability criteria are explicitly built into the method. Disproof could arise from textual evidence showing the tetrad applied to a Mediterranean fruit, archaeobotanical absence of coconut in the Indo-Pacific at the relevant time, genetic timelines incompatible with Plato’s era, ecological unsuitability, absence of relevant lexicon, spatial model misfits, or semantic proof that ἀλείμματα cannot mean plant oil. By specifying these pathways, the method ensures that the hypothesis remains open to rigorous testing rather than closed confirmation.

3. Workflow

3.1 Overview

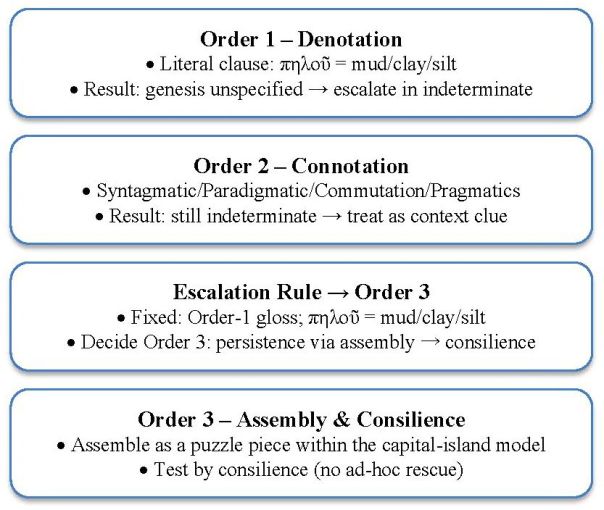

The methodological workflow for testing the coconut hypothesis proceeds through three analytic orders. This tiered design ensures that textual analysis is first anchored in the Greek passages, then expanded through pragmatic interpretation for Plato’s audience, and finally reconstructed with external evidence from ecology, archaeology, and cultural history. Each order contributes incrementally: Order-1 clarifies denotation, Order-2 uncovers communicative intention, and Order-3 integrates interdisciplinary evidence to yield a consilient synthesis.

3.2 Inputs & Outputs

The inputs to the workflow include the primary textual anchors from Critias 115a–b, key lexemes identified through philology, and comparative data from archaeobotany, genetics, and Austronesian cultural practices. The outputs vary by analytic order: Order-1 yields denotative baselines, Order-2 produces pragmatic insights into unfamiliarity and context clues, and Order-3 delivers a reconstruction tested through the puzzle piece catalogue, consilience scoring, counter-fruit challenges, and falsifiability checks. The workflow thus transforms raw text into structured hypotheses and measurable results.

3.3 Order-1 Workflow — Text Only

At the first order, the analysis remains strictly within the textual register. Here the aim is to extract philological baselines: the meaning of καρπὸς θαυμαστὸν τὸ μέγεθος and the tetrad of functions in Critias 115b. No assumptions about geography, botany, or culture are made at this stage. The coconut is not yet invoked; instead, the focus is on what the Greek text literally says. This provides a control level against which later interpretations can be tested.

3.4 Order-2 Workflow — Audience & Pragmatics

At the second order, the focus shifts to how the Egyptian priest’s words would have been understood by Solon and, later, by Plato’s audience. The unfamiliarity claim becomes central. The absence of a name and the reliance on a tetradic description function as deliberate context clues. For Solon, these clues pointed to a practical reality outside his cultural experience. For Plato’s readers, however, they connoted marvel and exotic abundance. Order-2 analysis thus explains why the priest spoke in functional terms and why the Greeks preserved those terms as marvels rather than as technical descriptions.

3.5 Order-3 Workflow — Reconstruction

At the third order, external evidence enters. The coconut tetrad is tested against the puzzle piece catalogue, where it interacts with other markers such as elephants, rice, legumes, climatic suitability, and the East-Mouth spatial model. Consilience scoring quantifies explanatory power, while the Counter-Fruit Test challenges coconut’s uniqueness by attempting substitutions with alternative species. Finally, falsifiability criteria ensure that the hypothesis remains open to disproof. Order-3 is therefore the stage where philology, pragmatics, ecology, and cultural history converge to produce a reconstruction that is both integrative and testable.

4. Integrated Analyses & Results

4.1 Overview & Conventions

This section integrates results from the three analytic orders into a single framework. At Order-1, we establish philological baselines from Critias 115a–b. At Order-2, we explore audience reception and pragmatic effects, including the Egyptian priest’s communicative strategy. At Order-3, we assemble textual, ecological, genetic, and cultural evidence into a consilient model. The coconut tetrad—hard rind, drink, food, oil—serves as the keystone of this integration. Conventions followed in this section include direct citation of Greek terms (with transliteration and literal translation), cross-reference to the puzzle piece catalogue, and explicit attention to negative testing and falsifiability.

4.2 Order-1 Outputs (Denotation, Philological Baseline)

At the first order, the task is to determine what the text literally says. In Critias 115a, Plato records the phrase καρπὸς θαυμαστὸν τὸ μέγεθος (karpòs thaumastòn tò mégethos)—‘fruit wondrous in size.’ This establishes magnitude as a defining feature. In 115b, the priest specifies: καρποὺς τοὺς σκληροφόρους, πόματα καὶ ἐδωδὰς καὶ ἀλείμματα παρέχοντας (karpoùs toùs sklērophórous, pómata kaì edodàs kaì aleímmata parékhontas)—‘fruits having a hard rind, providing drinks and meats and ointments.’ Taken together, the two clauses form a tetrad: husk/shell, drink, food, oil. At Order-1, no geographical or botanical assumptions are made, but the linguistic anomaly of such a functional tetrad already suggests deliberate instruction rather than poetic flourish.

4.3 Order-2 Outputs (Connotation & Pragmatic Effects)

At the second order, we ask how this description would have functioned in context. For Solon, the tetrad was a practical teaching device. The priest avoided a foreign loanword, instead supplying uses intelligible to a Greek but not associated with any familiar species. For Plato’s Athenian audience, however, the same inventory produced the interpretant of exotic marvel: a land whose fruits surpassed the Mediterranean norm. Thus, Order-2 analysis demonstrates that the tetrad was communicative in design, serving simultaneously as a bridge for Solon and a wonder for Plato’s readers.

4.4 Order-3 Outputs (Assembly & Consilience Tests)

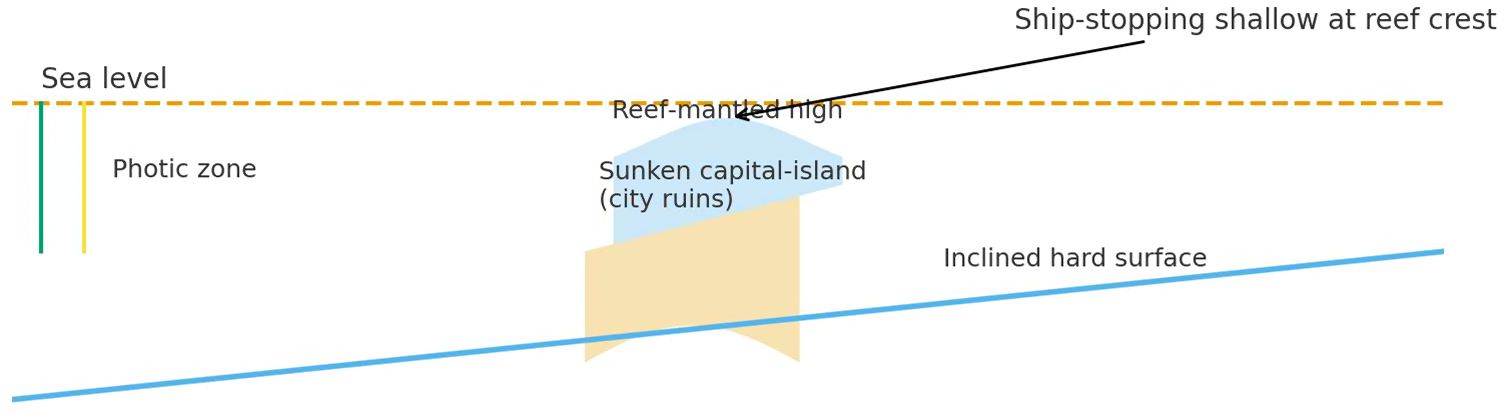

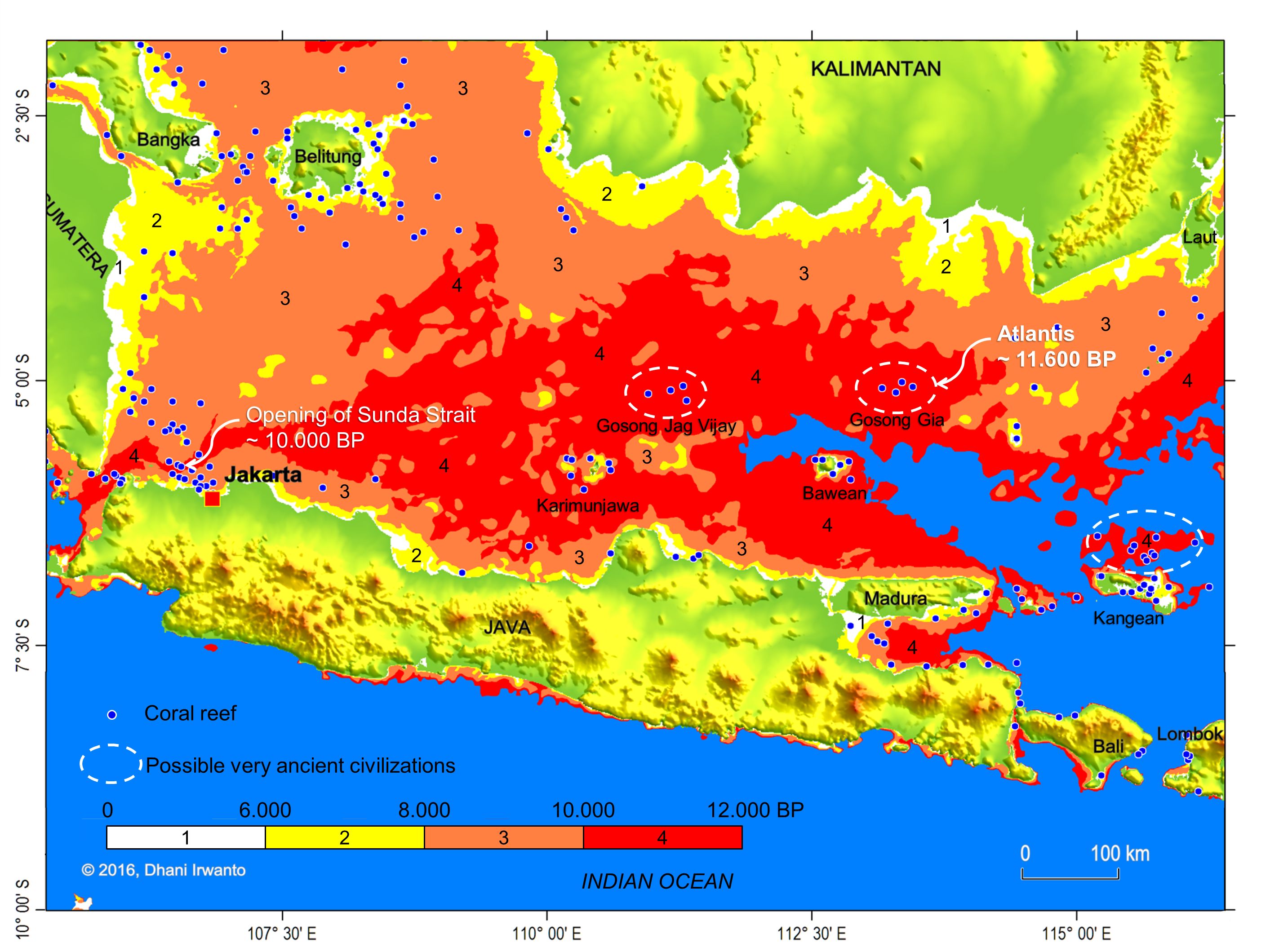

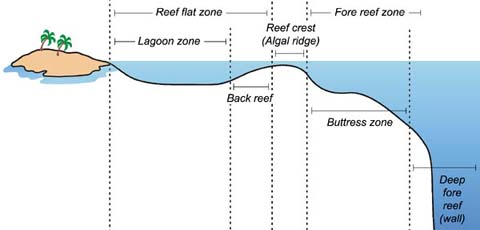

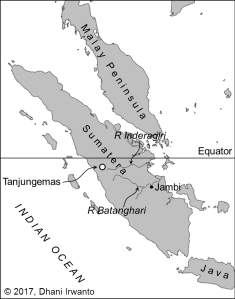

At the third order, external evidence is introduced. Archaeobotanical and genetic studies confirm dual domestication of coconut in South and Southeast Asia, with dispersal across the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Lexical evidence from Austronesian languages (niu, nyior, niyor) confirms antiquity and diffusion of coconut culture. Ecologically, the tropical-maritime belt of Sundaland aligns with climatic requirements for coconut cultivation. Spatially, the East-Mouth model situates coconut belts within canalizable reef corridors, offering logistical plausibility for trade and subsistence. When combined, these independent strands achieve consilience: coconut emerges as the only fruit that fits both text and environment.

4.5 Coconut as a Puzzle Piece

Coconut’s evidential strength lies in its dual role: it satisfies the philological tetrad exactly, and it integrates seamlessly with the wider puzzle piece catalogue for Sundaland Atlantis.

4.5.1 Puzzle Piece Catalogue

- A1 Elephants: Biogeographic marker consistent with Indo-Malayan fauna.

- A2 Rice + Legume Package: Staple subsistence pairing; complements coconut as lipid source.

- A3 Coconut Origin & Distribution: Diagnostic tetrad match; dual domestication and wide dispersal.

- A4 Climatic Suitability: Tropical–maritime ecology suitable for rice and coconut.

- A5 Coconut Tradition: Multipurpose uses; Austronesian lexicon (e.g., niu).

- A6 Spatial Model Fitting (East-Mouth + Nautical Corridors): Geometry of inner sea and mouth orientation; −60 m paleo-shoreline; reef gaps enabling coconut trade logistics.

- A7 Ancient Trans-Oceanic Contacts: Austronesian voyaging; coconut in pre-Columbian Panama.

- A8 Coral-Reef Shoal Chronology: Annular reef growth consistent with ‘shoal of mud.’

- A9 Timeline Discipline: Present-tense register; contemporaneous or remembered knowledge.

- A10 Legendization & Register: Transmission preserved as tetrad functions rather than name.

- A11 Toponymy & Lexical Parallels: Cognates (niu/nyior/niyor) reinforce continuity.

4.5.2 Consilience Scoring

Scoring rubric: 0–3 scale (0 absent; 3 specific), weighted by diagnostic power. Textual specificity and ecological fit carry the highest weights.

- R1 Textual Specificity: score = 3. Direct tetrad match + size clause (115a).

- R2 Biogeographic Fit: score = 3. Tropical Indo-Pacific, reef adjacency.

- R3 Archaeobotany/Genetics: score = 2–3. Dual domestication; early dispersal to both oceans.

- R4 Cultural Continuity: score = 3. Austronesian lexicon, craft traditions.

- R5 Spatial Model Fit: score = 2–3. East-Mouth geometry and paleo-shoreline compatibility.

- R6 Subsistence Coherence: score = 3. Rice–legume–coconut triad as carb, protein, lipid.

- R7 Timeline Discipline: score = 2. Present-tense plausible; conservative scoring.

- R8 Transmission Robustness: score = 3. Functional tetrad preserved across transmission.

Using a weighted 0–3 rubric, coconut consistently scores 2.7–2.9 across categories: 3 for textual specificity, 3 for biogeographic fit, 2–3 for archaeobotany/genetics, 3 for cultural continuity, 2–3 for spatial model fit, 3 for subsistence coherence, 2 for timeline discipline, 3 for transmission robustness. The composite indicates strong support.

4.5.3 Counter-Fruit Test

The counter-fruit test is designed to guard against confirmation bias by actively seeking alternative species that might satisfy the tetrad described in Critias 115b. Candidate fruits are selected from both Mediterranean and wider Old World contexts, including pomegranate, fig, date palm, breadfruit, calabash, and areca/betel nut. Each candidate is evaluated against the four functional criteria—hard rind, drink, food, and oil—using the same scoring rubric applied to coconut.

- Pomegranate: Has rind and juice but no oil; fails tetrad.

- Fig: No drink or oil; fails multiple functions.

- Date Palm: No natural drink; desert ecology misfits Sundaland.

- Breadfruit: Staple food but lacks drink and oil.

- Calabash: Hard shell container but little food, no drink, no oil.

- Areca/Betel Nut: Hard nut for chewing; no drink or meat.

All candidates fail at least two tetrad functions and misalign with Sundaland ecology.

4.5.4 Falsifiability

The coconut hypothesis can be disproven by several pathways:

- Textual Refutation: Greek passage where tetrad unambiguously applies to non-coconut fruit.

- Archaeobotanical Disproof: Evidence of coconut absence in Indo-Malaya during priest’s era.

- Genetic Contradiction: Revised chronology dating dispersal after Plato.

- Climatic Contradiction: Proof Sundaland climate unsuitable for coconut.

- Linguistic Void: Absence of coconut lexicon in early Austronesian strata.

- Spatial Misfit: Failure of East-Mouth model to support coconut corridors.

- Functional Mismatch: If ἀλείμματα cannot mean plant oil/ointment in this register.

4.5.5 Integrated Results

Coconut gains diagnostic strength not only through its tetradic alignment with Critias 115b but also within the broader puzzle piece catalogue applied to Sundaland Atlantis. Integrated with elephants, rice + legume, climatic suitability, and Austronesian trans-oceanic dispersal, coconut anchors the subsistence and cultural profile of the Atlantean plain.

The East-Mouth spatial model (−60 m shoreline, reef gaps, canalizable passages) provides environmental plausibility for coconut belts and trade logistics. Cultural continuities—lexicon (niu/nyior), craft traditions, and oil uses—further validate the tetrad as context clues supplied by the Egyptian priest.

Consilience tests score coconut highly across textual, ecological, and cultural lines. The Counter-Fruit Test shows that no Mediterranean or Near Eastern fruit satisfies the tetrad, and falsifiability criteria ensure the hypothesis remains testable. Together, coconut emerges as one of the strongest markers tying Plato’s agricultural description to the ecological realities of Sundaland.

By integrating catalogue, scoring, counter-fruit testing, and falsifiability, coconut is shown not only as a philological match but as a scientifically robust puzzle piece for situating Atlantis in Sundaland.

5. Discussion

5.1 Philology vs. Geographical Plausibility

A key tension in interpreting Critias 115a–b is balancing philological precision with geographical plausibility. On the philological side, the tetradic description—hard rind, drink, food, oil—is precise enough to exclude all Mediterranean fruits. Yet this precision alone is insufficient unless the ecology of the proposed locus can support coconut cultivation. Sundaland provides this ecological plausibility: a tropical, maritime environment where coconut thrives naturally and forms part of subsistence and culture. Thus, philology and geography converge, rather than conflict, in the Sundaland framework.

5.2 Timeline Alignment

The priest’s words to Solon are expressed in the present tense, suggesting immediacy: the land ‘bore forth’ its fruits at the time of narration. This raises methodological questions: was the priest describing a contemporary reality known through trade, or a memory of a more ancient past? Archaeobotanical and genetic evidence shows that coconuts had already dispersed widely across the Indo-Pacific by the second millennium BCE, well before Solon’s era. Thus, both interpretations remain viable: the description could reflect either living knowledge circulating in Egypt or a fossilized tradition preserved from deep antiquity. In either case, the present tense functions as a rhetorical device to render the description vivid and authoritative.

5.3 Legendization in Transmission

The path from Egyptian priest to Solon to Plato inevitably introduced processes of transmission and adaptation. One such process is legendization: functional descriptions become framed as marvels, and concrete agricultural facts acquire the aura of myth. The coconut tetrad is an exemplary case. For the priest, it was a set of context clues designed to bridge cultural unfamiliarity. For Solon, it conveyed exotic practicality. For Plato, retelling to his audience, it became an emblem of Atlantis’ strangeness and abundance. Recognizing this process of legendization allows us to explain why a foreign fruit survives in Greek literature not as a loanword but as a functional tetrad that borders on mythic imagery.

5.4 Integration with Other Puzzle Pieces

Coconut does not stand in isolation. It aligns with other puzzle pieces: elephants as faunal markers, rice and legumes as staples, coral-reef shoals as geological features, and the East-Mouth spatial model as geographical geometry. Together, these pieces form a coherent picture of a tropical, maritime plain consistent with Plato’s narrative. The coconut tetrad, by virtue of its specificity and uniqueness, strengthens the catalogue rather than merely adding to it. In consilience, each puzzle piece increases the explanatory coherence of the whole hypothesis.

5.5 Risks, Confounds, and Methodological Safeguards

No reconstruction is free from risks. One risk is over-interpretation: forcing a unique description to fit coconut while ignoring alternative explanations. Another confound is anachronism: projecting later coconut traditions backward into Plato’s era. To mitigate these, the Counter-Fruit Test ensures that alternatives are fairly considered, and falsifiability protocols set boundaries for disproof. By explicitly acknowledging risks and setting controls, the coconut hypothesis remains methodologically robust rather than speculative.

In sum, the discussion demonstrates that coconut as the referent of Critias 115b is not an arbitrary choice but a disciplined inference: it aligns philology with ecology, reconciles timeline uncertainties, accounts for legendization in transmission, and integrates seamlessly into the wider consilience framework of Sundaland Atlantis.

6. Conclusion

The coconut tetrad of Critias 115b—hard rind, drink, food, and oil—emerges as one of the most decisive context clues offered by the Egyptian priest to Solon. Unlike metaphorical flourishes or symbolic exaggerations, this description is concrete, utilitarian, and unique. It corresponds precisely to the material profile of the coconut, a plant outside the experience of Classical Greece yet central to the tropical ecologies of Sundaland. The tetrad thereby functions as both a linguistic fossil and a cultural bridge: it preserved the memory of Atlantis’ agricultural reality in a form intelligible, though exotic, to Solon and Plato’s audience.

Through the application of semiotics, linguistics, philology, and interdisciplinary consilience, the coconut has been tested and confirmed as a robust puzzle piece within the Sundaland–Atlantis framework. Order-1 analysis established the philological baseline; Order-2 clarified the communicative role of unfamiliarity and context clues; Order-3 integrated ecological plausibility, genetic timelines, cultural traditions, and spatial models. Each analytic order reinforced the others, yielding a convergent result. The coconut is not an arbitrary identification but the most parsimonious solution to the textual problem posed by Critias 115b.

Furthermore, by subjecting the hypothesis to counter-fruit testing and falsifiability criteria, the analysis remains scientifically open. Alternative candidates fail to replicate the tetrad, while clear pathways for disproof ensure that the coconut argument does not collapse into circular reasoning. This methodological transparency strengthens the case rather than weakens it.

In broader perspective, the coconut integrates seamlessly with other puzzle pieces: elephants as faunal markers, rice and legumes as staples, coral-reef shoals as geological features, and the East-Mouth spatial model as a navigational geometry. Together, these strands weave a coherent picture of Sundaland as the plausible cradle of Atlantis. The coconut, by virtue of its tetradic uniqueness, serves as a keystone in this reconstruction. It anchors Plato’s text to the ecological and cultural realities of Southeast Asia, transforming a mythic marvel into a testable historical clue.

The conclusion, therefore, is not merely that the coconut fits Plato’s words, but that it does so with explanatory power unmatched by any alternative. It stands as a decisive consilient marker: a fruit wondrous in size, bearing a hard rind, providing drink, food, and oil—exactly as the Egyptian priest described. In this convergence of philology, ecology, and culture, the coconut illuminates both the text of *Critias* and the deeper history of Sundaland Atlantis.

References

- Luc Baudouin and Patricia Lebrun, Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) DNA studies support the hypothesis of an ancient Austronesian migration from Southeast Asia to America, 2008. Springer Link, March 2009, Volume 56, Issue 2, pp. 257-

- Bee F. Gunn, Luc Baudouin and Kenneth M. Olsen, Independent Origins of Cultivated Coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) in the Old World Tropics, 2011. PLoS ONE 6(6): e21143. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021143.

- Jones TL, Storey AA, Matisoo-Smith EA and Ramirez-Aliaga JM, Polynesians in America: pre-Columbian contacts with the New World, 2011. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Luc Baudouin, Bee F. Gunn and Kenneth M. Olsen, The presence of coconut in southern Panama in pre-Columbian times: clearing up the confusion, 2013. Annals of Botany: doi:10.1093/aob/mct244.

- Saussure, F. de. (1916/1983). Course in General Linguistics (trans. R. Harris). London: Duckworth. [Foundational dyadic model; cited per synthesis in Irwanto (2025), Note 4].

- Peirce, C. S. (1992–1998). The Essential Peirce: Selected Philosophical Writings (Vols. 1–2). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Triadic sign–object–interpretant; per Note 4].

- Barthes, R. (1957/1972). Mythologies (trans. A. Lavers). New York: Hill and Wang. [Orders of signification; per Note 4].

- Barthes, R. (1964/1967). Elements of Semiology (trans. A. Lavers & C. Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. [Semiotic method; per Note 4].

- Barthes, R. (1977). Image–Music–Text (ed. & trans. S. Heath). New York: Hill and Wang. [Applications to text analysis; per Note 4].