A testable synthesis of classical sources, resource geography, monsoon routing, and toponymy.

Related articles:

- Aurea Chersonesus is in Sumatera

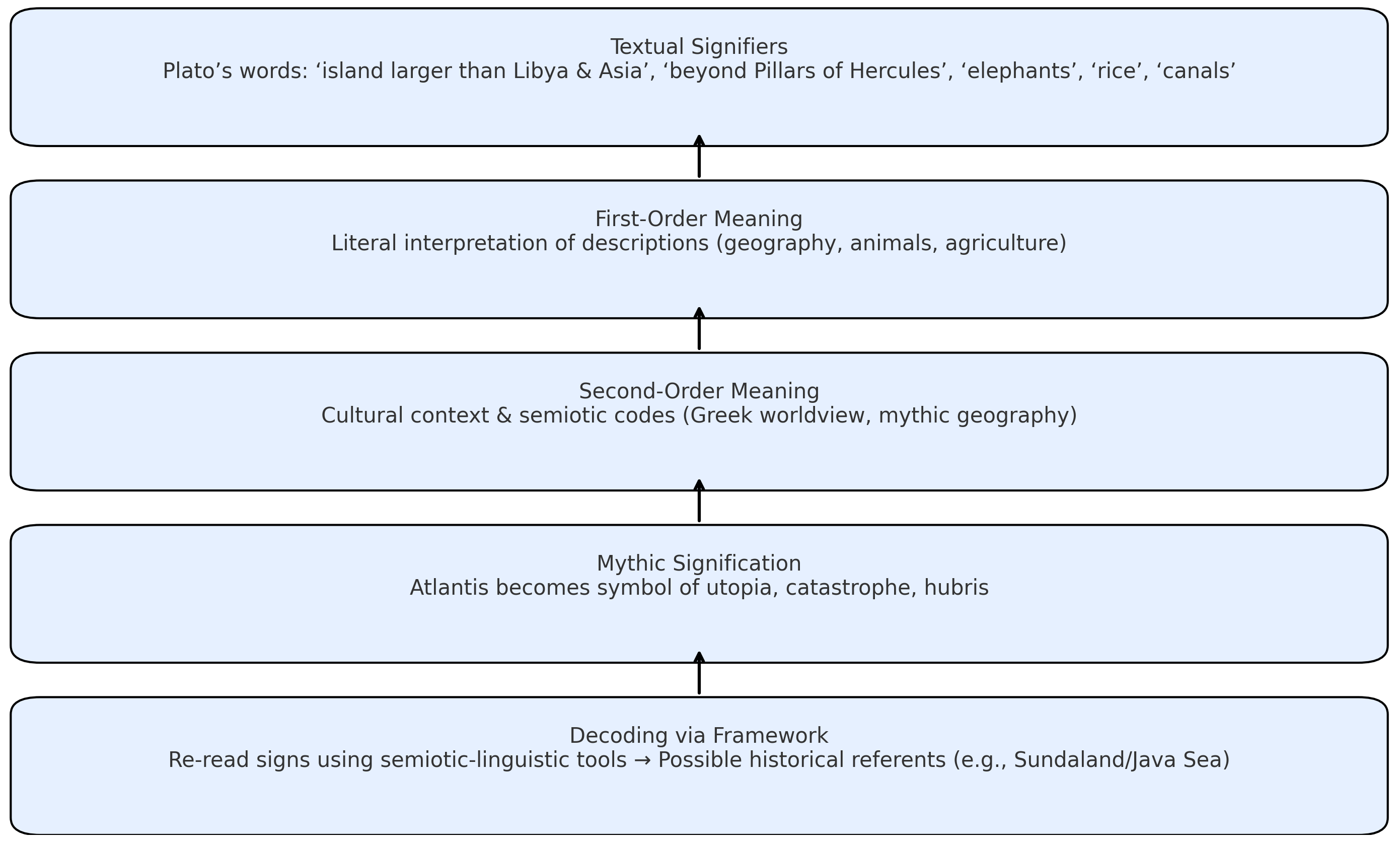

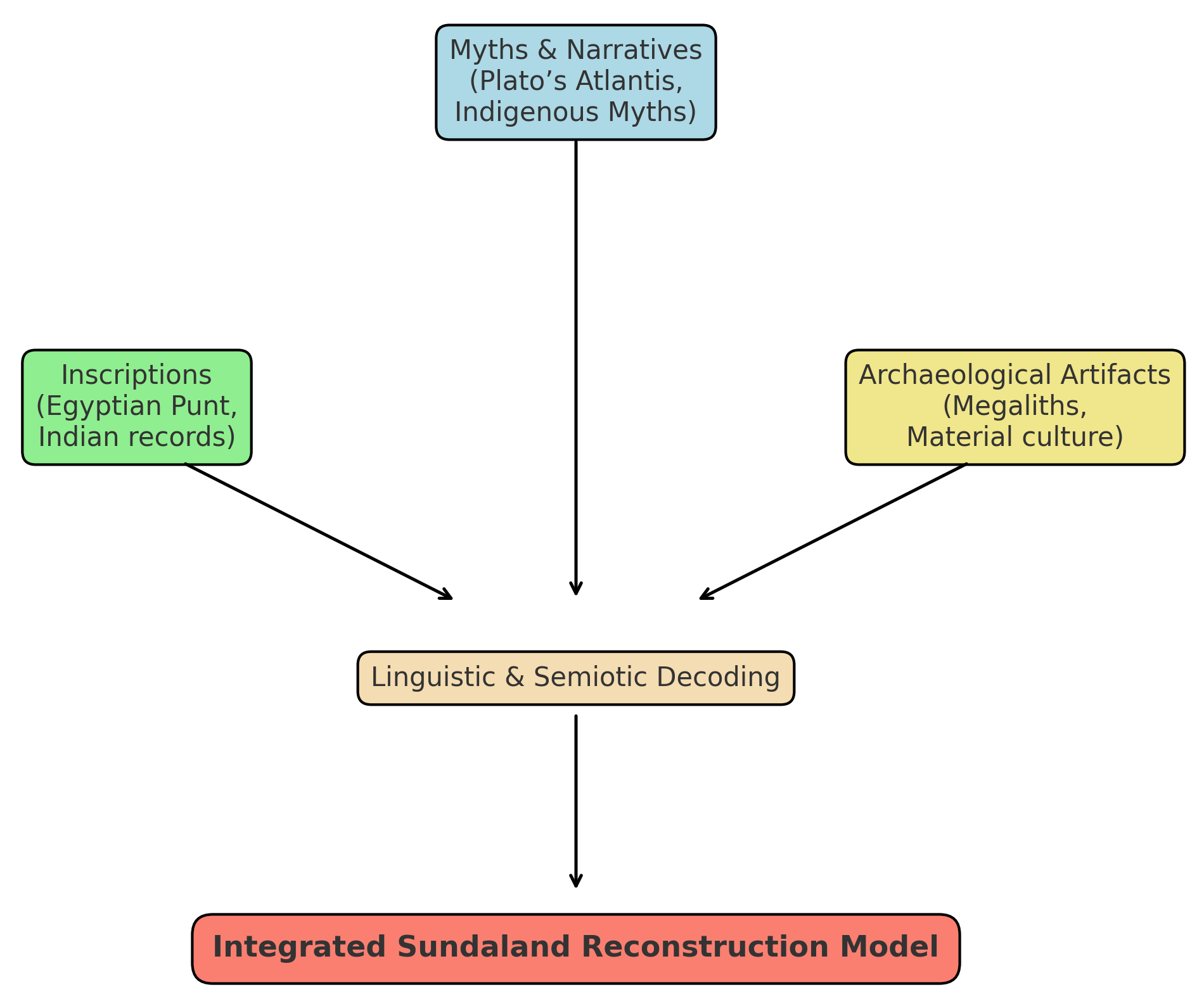

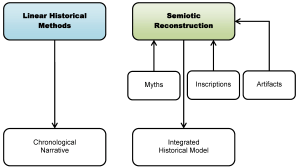

- Decoding Signs of the Past: A Semiotic and Linguistic Framework for Historical Reconstruction

- Research paper

A research by Dhani Irwanto, 30 August 2025

Abstract

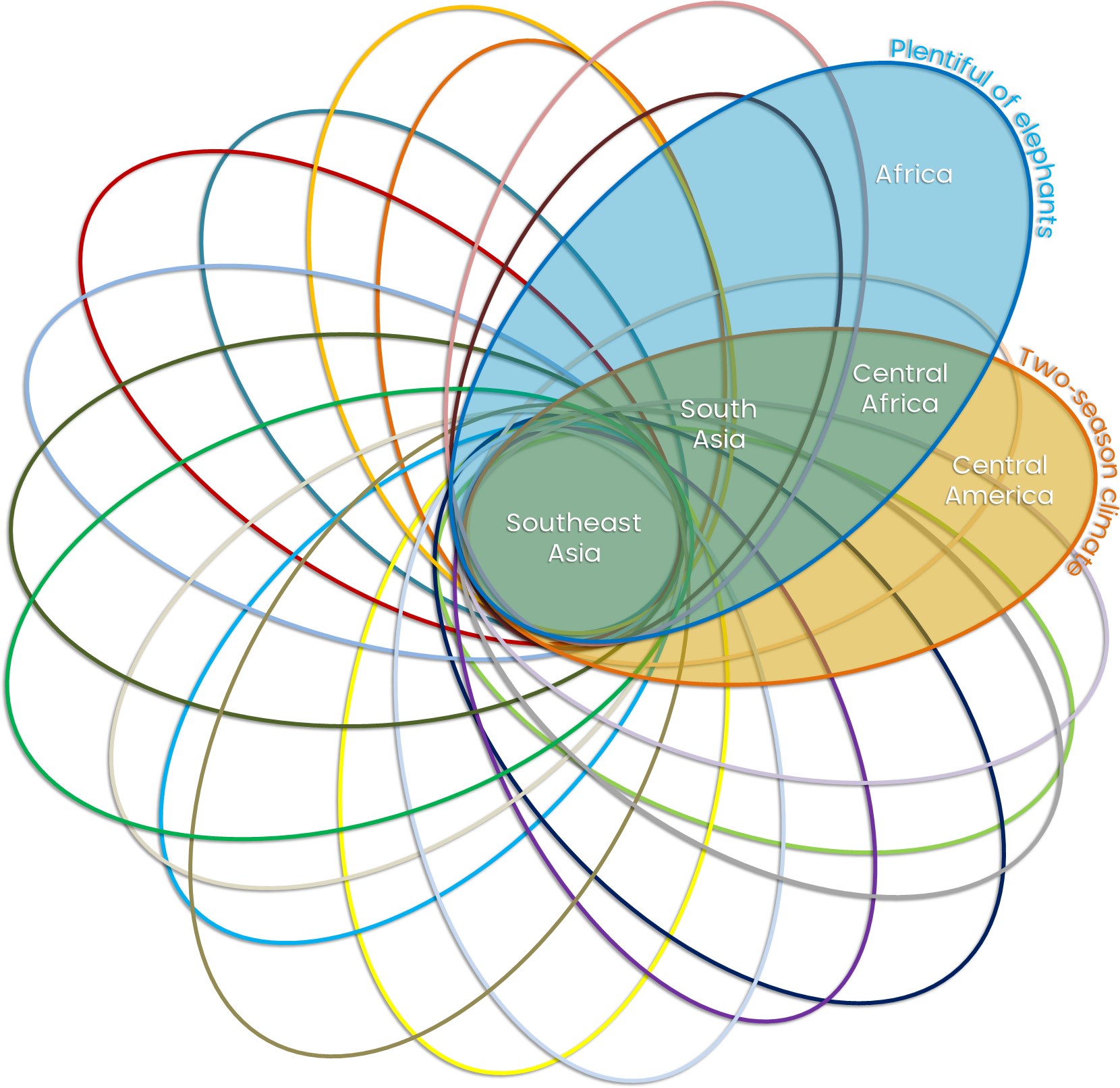

Classical geographers—most prominently Claudius Ptolemy—refer to the Aurea Chersonesus (“Golden Peninsula”), long equated with the Malaya Peninsula. This study re-examines that consensus by triangulating Greco-Roman texts, Indic labels (Suvarṇabhūmi, Suvarṇadvīpa), resource geography, maritime routing, and toponymy. We argue that Ptolemy’s χερσόνησος functions as a scale-normalized, bi-littoral construct: a gold- and tin-forward corridor spanning both shores of the Strait of Malacca. Read geometrically, Ptolemy Book 1, ch. 14 treats the first leg parallel to the equator and the second toward south-and-east, consistent with seasonally asymmetric monsoon routing. New contributions include: (i) a Sumatra-centered toponymic thread around Tanjung Emas (“Golden tanjung” —a projecting landform that may be marine or fluvial), accessible from the Bay of Berhala via the Batang Hari corridor and interpreted via metonymy (tanjung → regional chersonesos); and (ii) equator-ambiguous latitude tests combined with an alternative-inclusive crosswalk of Ptolemaic names. Results show that several Sumatra–Batang Hari alignments outperform canonical Malaya Peninsula placements on the latitude metric, and this advantage persists when multiple Malaya Peninsula alternatives are allowed. The framework preserves viable Malay identifications while motivating a Sumatra-focused component of the “Golden” label. It yields falsifiable predictions for archaeometallurgy (interior-to-estuary transects), toponymy audits (paired placements with winners), and sailing-time modeling (monsoon-aware residuals), providing a concrete agenda to confirm or revise the bi-littoral “Golden Corridor” model.

Keywords

Aurea Chersonesus; Golden Chersonese; Suvarnadvīpa; Sumatra; Malaya Peninsula; Ptolemy; Indian Ocean trade; Srivijaya; historical cartography; gold metallurgy; Batang Hari River; Tanjung Emas.

1. Introduction

In classical geography, the Aurea Chersonesus (“Golden Peninsula”) occupies a prominent position at the eastern edge of the Indian Ocean world. The most influential canonical description is found in Ptolemy’s Geography (2nd century CE), whose toponymic lists and coordinate grid—despite known distortions—shaped the medieval and early modern image of the Far East. For over a century of modern scholarship, the Golden Chersonese has been equated with the Malaya Peninsula, a view championed by Gerini, Wheatley, Linehan and others. This mapping is intuitive: Ptolemy’s Greek label chersonēsos refers to a peninsula, and the Malaya Peninsula is the most conspicuous salient in the region.

Yet parallel South and Southeast Asian traditions preserve complementary designations: Suvarṇabhūmi (“Land of Gold”) and Suvarṇadvīpa (“Island of Gold”). The latter is repeatedly linked to Sumatra (Indonesia)—a literal island long noted for its alluvial gold in the Minangkabau interior. Chinese and Arabic itineraries later anchor Srivijaya-era commerce along the Malacca–Andaman corridor, while archaeometallurgical and historical mining records underscore dense gold and tin provinces distributed across the Sunda Shelf. Together these strands suggest that ancient informants may have perceived a trans-Strait gold zone rather than a single, peninsular monocenter.

Classical writers already associated the Far East with Chryse/Aurea (“golden”) long before Ptolemy. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea places an island called Chryse at the extreme eastern limit “under the rising sun,” a node for fine tortoise-shell and gold-related trade items. Pliny mentions both a promontory Chryse (Promunturium Chryse) and the islands Chryse and Argyre beyond the Indus, keeping “golden” toponymy in play as either cape or island. Pomponius Mela likewise lists Chryse and Argyre as islands, the former with “golden soil,” in his Far Eastern notices. Later poetic geographies such as Dionysius Periegetes (Periegesis) and Avienus (Ora Maritima) preserve the motif of a golden island at the sunrise margin. In South and Southeast Asian sources, Suvarṇabhūmi and Suvarṇadvīpa recur as Indic labels for a “golden land/island”; the Mahāvaṃsa records missions “to Suvarṇabhūmi,” while the Padang Roco (1286 CE) inscription explicitly names Swarnnabhūmi/ Suvarṇabhūmi in a Jambi–Dharmāśraya context, and the Nagarakretagama (1365) situates this golden geography within wider Javanese–Sumatran political space. For consolidated discussion, see the author’s earlier summary.

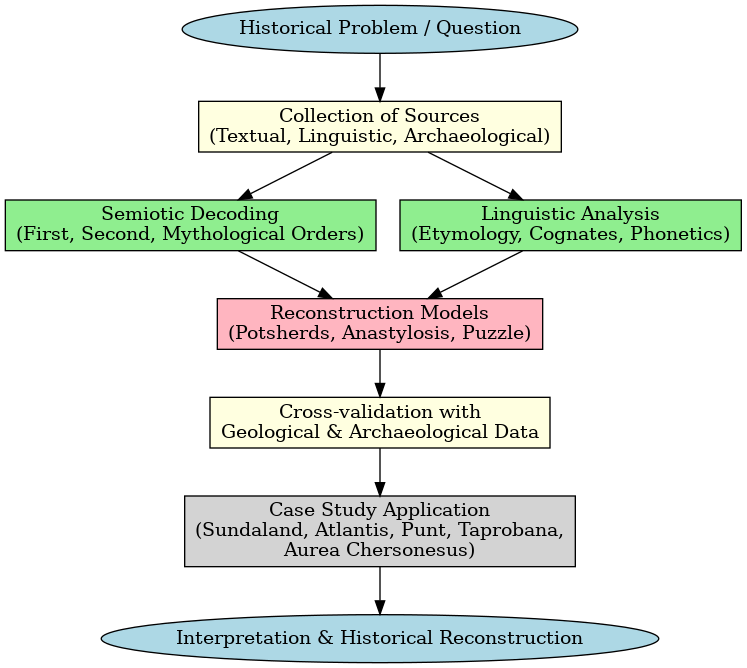

This paper reframes Aurea Chersonesus through a consilience framework that explicitly integrates: (i) textual–cartographic analysis of Ptolemy’s descriptive geometry and errors, (ii) resource geography (gold and tin provinces), (iii) monsoon-season maritime network modeling, and (iv) toponymy and ethnolinguistics, including a Sumatra-specific thread around Tanjung Emas (“Golden tanjung”) and the Batang Hari River system on Sumatra’s east-flowing watershed. We also incorporate authorial contributions from Sundaland research—specifically Irwanto’s works and website articles—as primary references and as a structured hypothesis to be tested alongside mainstream interpretations. We contend that a bi-littoral Golden Corridor model better explains the overlap between the Greco-Roman “peninsula” label and the Indic memory of an “island of gold,” while remaining open to strict falsification.

This study extends work within the Sundaland research program (2010–present).

Background and prior scholarship.

The standard view equating Aurea Chersonesus with the Malaya Peninsula rests on three pillars: (1) the literal meaning of chersonēsos as “peninsula,” (2) sequences of toponyms in Ptolemy and later writers that seem to fit the Malaya Peninsula littoral, and (3) a century of careful philological and cartographic work that codified these identifications. Against this, critics have flagged well-known features of Ptolemy’s geography: systematic longitude compression, variable latitude accuracy, and the compilation of sailing intelligence from merchants whose reports were stitched into schematic coastlines. The possibility of feature conflation is amplified at the eastern Indian Ocean rim, where two substantial coastlines—the Malaya Peninsula and Sumatra—straddle a narrow strait threaded by seasonal monsoon routes.

In parallel, Indian and Southeast Asian textual memories invoke Suvarṇabhūmi (Land of Gold) and Suvarṇadvīpa (Island of Gold), with the latter specifically resonant with Sumatra. Historians of metallurgy and early Southeast Asian trade have documented significant gold exploitation in Sumatra’s highlands and extensive tin belts on both shores. A consolidated review of Sumatra’s long history of gold production—artisanal, colonial, and modern—appears in van Leeuwen (2014), with a journal update in van Leeuwen (2022). The net result is an evidentiary landscape that supports either a Malaya Peninsula-only model or a broader, paired-shore model—leaving room for careful re-evaluation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Sources and consilience design

- Textual–cartographic analysis: reading Ptolemy’s coastal descriptors (promontories, gulfs, river mouths, sailing distances) against modern coastlines, while explicitly modeling the distortions of his coordinate grid.

- Resource geography: mapping classical references to “gold” and “tin” onto known ore provinces (Sumatra interior, Malaya Peninsula belts, western Borneo) and comparing them with riverine access to export points.

- Maritime network modeling: reconstructing monsoon-dependent sailing legs and currents across the Andaman–Malacca corridor to assess whether a Malaya Peninsula-only or a Malaya Peninsula–Sumatra model better explains reported distances and stopovers.

- Toponymy and ethnolinguistics: re-auditing canonical identifications on the Malaya Peninsula side and testing Sumatra-side candidates, with special attention to hydronyms and ancient waypoints along the Batang Hari system; including a linguistic parallel between “Aurea Chersonesus” and “Tanjung Emas” (Golden tanjung).

2.2 Ptolemy’s coordinate system and latitude handling

Ptolemy lists a sequence of coastal features—capes, gulfs, islands—accompanied by latitudes and longitudes aligned to an Alexandrian prime meridian. The transmission of these coordinates is uneven: longitudes are systematically compressed; latitudes are more stable but still subject to copyist error and observational imprecision. For the Golden Chersonese, the relevant coordinates cluster near the equator—within a handful of degrees on either side—consistent with either the Malaya Peninsula’s southern sector or Sumatra’s east-coast theater. This equatorial clustering is not dispositive on its own, but it reduces the discriminating power of latitude while preserving an important constraint for any re-identification.

A key methodological move, therefore, is to treat Ptolemy’s coordinates as weak constraints to be combined with descriptive geometry (e.g., the order of features along a voyage) and sailing times. When this is done, several ambiguities arise that are better resolved by admitting Sumatra’s ports and promontories into the candidate set, rather than forcing a Malaya Peninsula-only mapping.

3. Results

3.1 Quantitative fit to Ptolemy’s latitudes

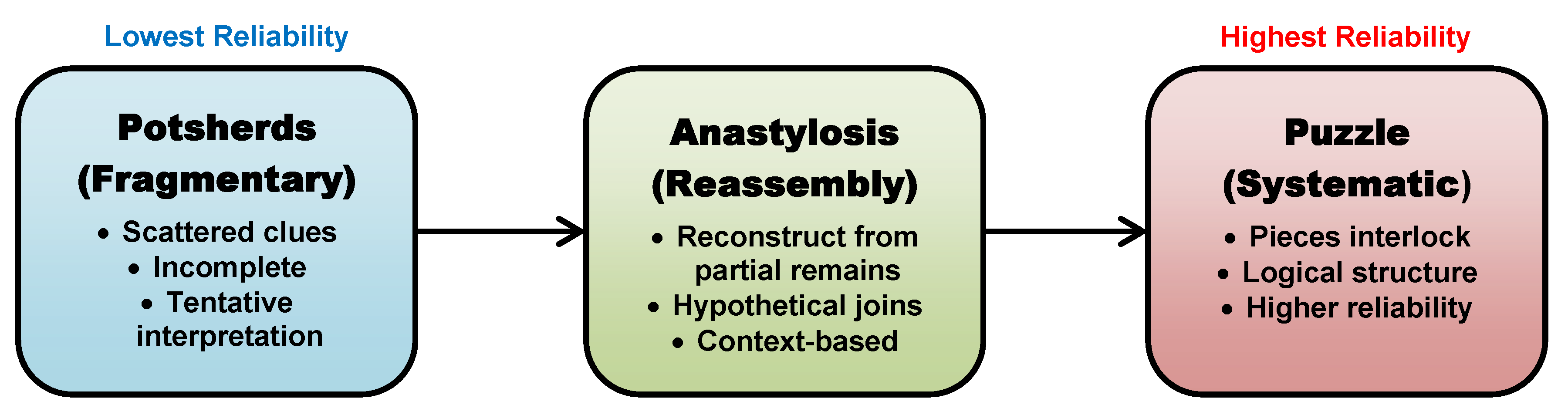

Latitude comparison with Ptolemy. Using our Sumatra (Batang Hari) coordinates and mainstream Malaya Peninsula placements, we computed residuals per toponym: |Δφ| (absolute signed difference). In the comparison (Table 3), the overall means favor the Sumatra placements as the modal ‘winner’.

3.2 Resource geography: gold, tin, and river access

An independent constraint from ores and rivers. The Sumatran interior (Minangkabau–Barisan) preserves a long record of alluvial and hard-rock gold, with major drainages trending east to the Batang Hari and the Bay of Berhala; historical syntheses outline a province-scale gold belt extending through the central highlands (van Leeuwen 2014; 2022). By contrast, the Malaya Peninsula is classically associated with prolific tin belts (with gold occurrences present but secondary). For distant compilers, such a bi-littoral metalscape could easily coalesce into a generalized “golden” reputation, irrespective of the precise ore mix on each shore.

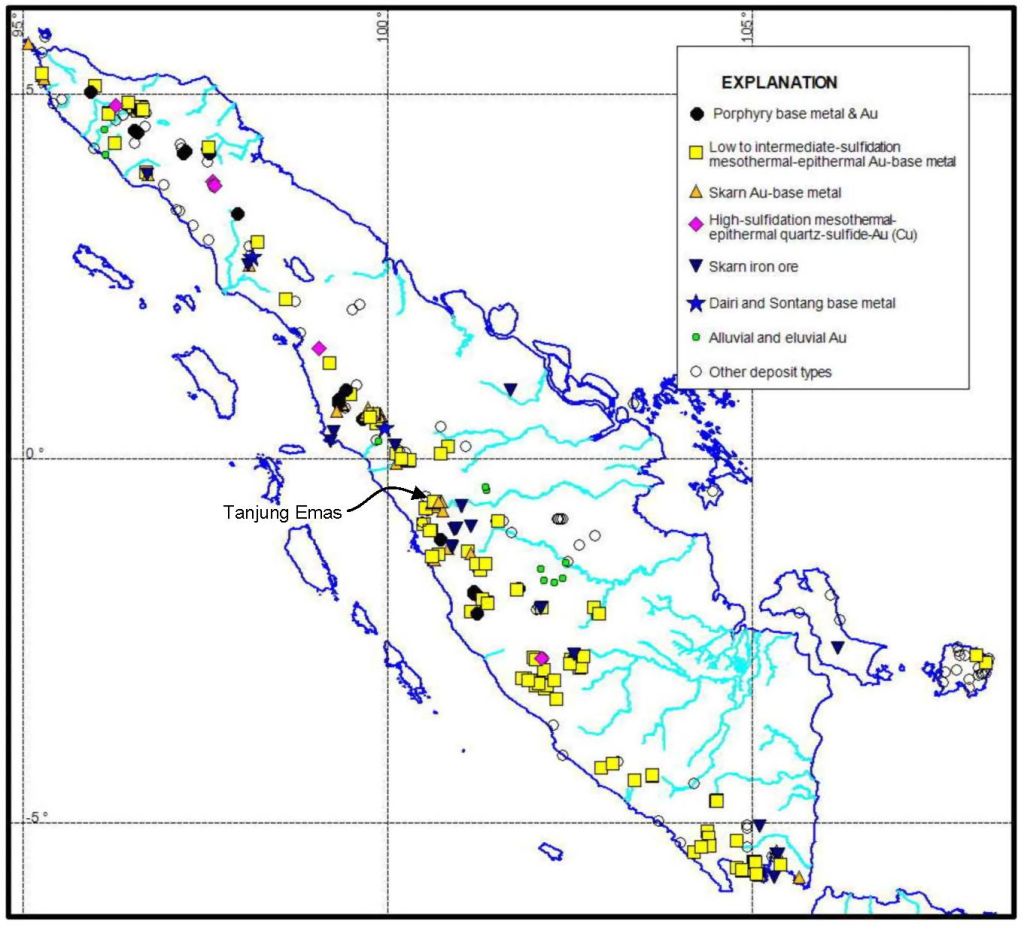

A natural conveyor on the Sumatra side. The Batang Hari functions as a low-gradient corridor from interior sources to estuarine export nodes. In this configuration, Muara Sabak anchors access from the Bay of Berhala, while levee ridges, relict channels, and terrace margins along the lower–middle river offer plausible staging points for beneficiation and transshipment. Even allowing for seasonal constraints, interior-to-coast movement is mechanically feasible in antiquity and consistent with the corridor model proposed here (see Figure 2 for metallogenic context; Table 1 for gazetteer entries).

Implication for the “Golden” label. Read together, (i) a gold-forward Sumatran interior efficiently coupled to an east-draining river system, and (ii) a tin-forward Malay littoral participating in the same exchange circuits, provide a resource-hydrology mechanism by which a bi-littoral corridor could be perceived and named as Aurea. This pattern does not negate canonical Malaya Peninsula placements; it adds a Sumatra-side contribution that is independently motivated by ore belts and river access, and is testable against the toponymic cross-walk (Table 2) and latitude residuals (Table 3).

For historical overviews of Sumatra’s mining districts, see van Leeuwen 2014; 2022.

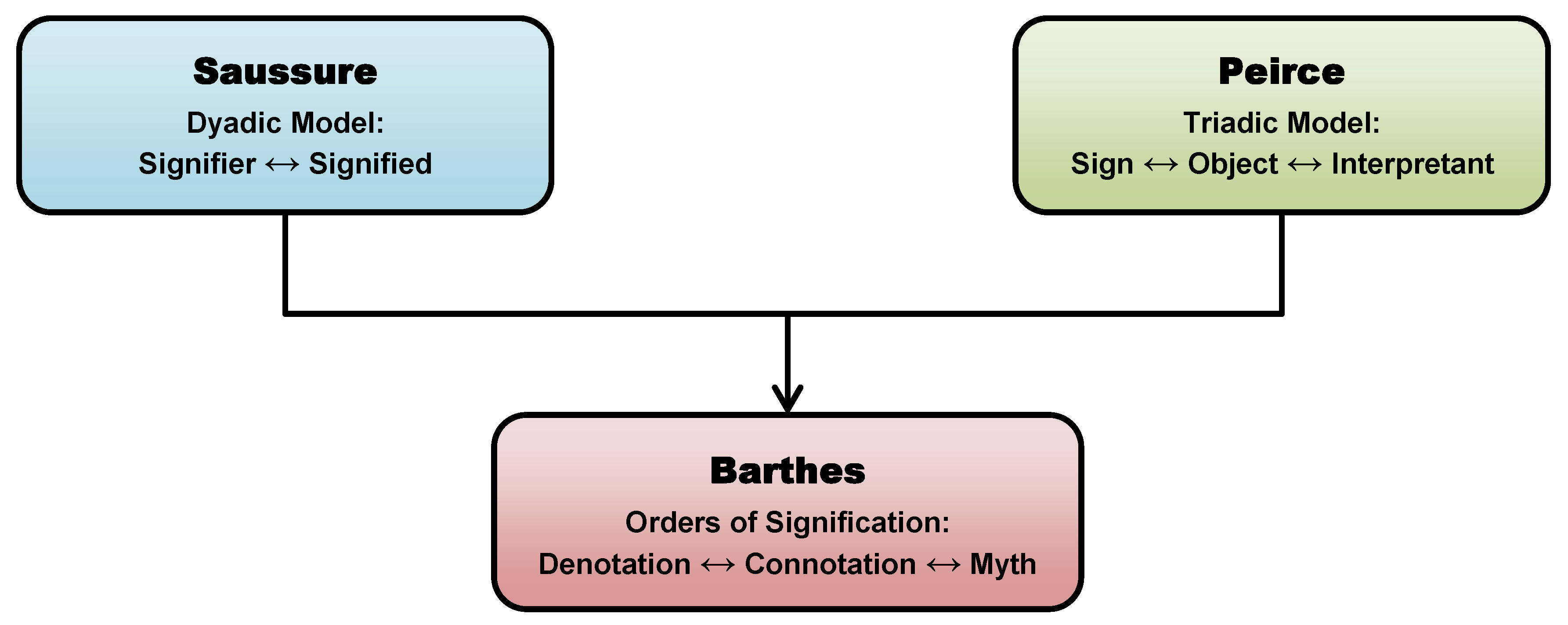

3.3 Toponymy and linguistic signals

Indic labels and scale. Sources preserve two overlapping labels—Suvarṇabhūmi (“land of gold”) and Suvarṇadvīpa (“island of gold”). While dvīpa literally means “island,” it is scale-flexible in Indic usage (cf. Jambudvīpa for the Indian subcontinent). In our context, the island reading maps neatly onto Sumatra, without excluding broader macro-regional senses that Greco-Roman compilers might have normalized into a single peninsular label.

Malayic tanjung and Greek chersonēsos. In Old Malay/Malayic usage, tanjung denotes a projecting landform in marine, lacustrine, or fluvial settings. The Tanjung Emas district (“Golden tanjung”) is best understood as a promontory-like high ground along the lower surrounding floodplain rather than a marine cape. This semantics resonates with Ptolemy’s chersonēsos—a macro-regional label—and allows a metonymic elevation whereby a renowned local tanjung contributes the name for a wider “golden” littoral. Geographically, the Tanjung Emas hinterland links directly to the Batang Hari corridor, enabling access from the Bay of Berhala inland to the Minangkabau gold belt.

Re-auditing Ptolemy’s names. Ptolemy’s lists of capes, gulfs, and river mouths include several non-consensus identifications. Our approach is a structured toponymy audit across both shores: we prioritize hydronyms, tanjung-promontories, emporia/market towns, and gold-semantic lexemes; we score each candidate on phonology/orthography, morphology/semantics, latitude residuals, and route coherence with neighboring entries. Ties within narrow thresholds (e.g., ≤0.2° latitude; ≤1 day sailing) are recorded as paired candidates, and a “winner” is declared only when one side clears both thresholds. Results are summarized in Table 2 (crosswalk) and Table 3 (latitude/residual tests), with notes on metonymy and potential conflations (a famed cape/emporion naming a wider reach).

Next evidentiary steps. These linguistic placements remain hypotheses to be tested against dated epigraphy, early Malay/Old Javanese/Sanskrit forms, and early Chinese notices around the rise of Śrīvijaya. Convergent support from these lines—together with the resource-hydrology fit and route modeling—would raise the probability of a Sumatra-linked component in the ancient “Golden” label without negating canonical Malaya Peninsula-littoral placements.

3.4 Maritime networks and monsoon timing

Findings from the latitude/residual tests. Across the full set and the near-equator subset, Sumatra–Batang Hari alignments outperform canonical Malaya Peninsula placements. Allowing multiple Malaya Peninsula alternatives per name does not erase this advantage. (See Table 3; cross-references in Table 2.)

Caveats and robustness. Ptolemy’s values carry observational/transcriptional noise, and several Malaya Peninsula identifications remain non-unique. Our residuals are comparative indicators, not absolute fits. Even so, the pattern holds across analysis slices and modeling choices (single-option vs. alternative-inclusive tallies), supporting a Batang Hari-centric reading of several toponyms.

Monsoon-structured routing. The Andaman–Malacca–Java Sea system is seasonally asymmetric. With NE/SE monsoon reversals, westbound and eastbound legs differ in coast selection, sailing times, and stopovers. Interpreted with the Ptolemy Book 1, ch. 14 geometry (first leg parallel to the equator; second south-and-east), the bi-littoral model frequently reduces sailing-time residuals (Figure 4): pilots could hug windward or leeward shores by season, cargo, and political control. On the Sumatra side, the Bay of Berhala → Batang Hari entrance provides a natural gateway; on the Malaya Peninsula side, routes favor tin-rich coastal settlements and established emporia.

Implication. Flexible, seasonally tuned routing is exactly what a “Golden Corridor” predicts: resource collection, transshipment, and long-distance export distributed across both coasts, with the Batang Hari corridor supplying a persistent Sumatran component without displacing viable Malaya Peninsula placements.

3.5 Case study: Batang Hari corridor and the Bay of Berhala

Physical setting and logistics. The Batang Hari drains a broad swath of the Minangkabau–Barisan highlands and debouches to the Bay of Berhala. Its east-trending, low-gradient lower course functions as a natural conveyor from interior gold districts to estuarine exchange nodes (see Figure 2 for metallogenic context). Muara Sabak anchors the mouth; levee ridges, relict channels, and terrace margins along the lower–middle river provide plausible staging points for beneficiation and transshipment, at least seasonally.

Toponymy anchor: Tanjung Emas. The district name Tanjung Emas (“Golden tanjung”) preserves a promontory-linked economic memory. In Malayic usage, tanjung denotes a projecting landform (marine or fluvial); here it fits a promontory-like high ground on the lower surrounding floodplain. Read alongside Greek χερσόνησος (chersonēsos, “peninsula”), this supports a metonymic elevation from a local landmark to a regional ‘golden’ littoral.

Ptolemaic cross-walk signals. Within this theater, several promontoria, sinus/gulfs, river mouths, and islets in Ptolemy’s lists admit tentative Sumatra-side correspondences when screened by (i) latitude residuals (Table 3), (ii) onomastic plausibility (Table 2 notes), and (iii) route coherence under the Ptolemy Book 1, ch. 14 geometry (first leg parallel to the equator, second south-and-east; see Figure 4). We do not sanctify any single identification; rather, we show that a Batang Hari-centric mapping is geographically and semantically coherent within Ptolemy’s equatorial constraints.

Near-term tests. Three checks can raise/lower the case:

(i) Archaeometallurgy along interior→estuary transects (levee/terrace nodes; microresidues, Au–Ag fines, Hg spikes; targeted dating);

(ii) Toponymy audit with scored paired placements (phonology/semantics + |Δφ| + route context);

(iii) Sailing-time residuals comparing Malaya Peninsula-only vs Malaya Peninsula–Sumatra models across monsoon windows (Figure 4). Convergent positives would strengthen a Sumatra-linked component in the ancient “Golden” label without displacing viable Malaya Peninsula identifications.

4. Discussion

4.1 Synthesis: the bi-littoral ‘Golden Corridor’ model

We triangulate the Ptolemaic dossier from three strands: (i) Greco-Roman “Chryse/Aurea” notices (promontory and island traditions), (ii) Indic labels Suvarṇadvīpa/Suvarṇabhūmi, and (iii) material proxies for gold production and exchange in Sumatra. Travel and scholastic itineraries (e.g., Samaraiccakaha; Atīśa, Dharmapāla, Vajrabodhi, Dharmakīrti in Suvarṇadvīpa) keep Sumatra in view; some readers also connect Josephus/Ophir to the Aurea Chersonesus stream. Archaeologically and historically (Lebong Donok/Lebong Tandai, Jambi paleo-alluvials, Salido, Kotacina), the record is consistent with a corridor of gold working rather than a single peninsular monocenter.

We synthesize these into a parsimonious bi-littoral model:

(1) Knowledge compression. Greco-Roman compilers normalized merchants’ reports into schematic forms. A bi-coastal gold/tin region framed by a narrow strait could be compressed into a single “Golden Peninsula” (χερσόνησος) even when source reports alternated between island and peninsula descriptions.

(2) Equatorial constraint. Ptolemy’s latitudes for the Golden Chersonese cluster near the equator. Both a southern Malay salient and an east-Sumatra promontory system satisfy this, so latitude alone does not decide; we therefore compare residuals (Table 3).

(3) Resource–hydrology fit. Sumatra’s gold-bearing highlands drain efficiently to the Batang Hari export gateway; the Malay Peninsula side contributes tin (and gold) via its own river access. The Malacca corridor integrates both shores into long-distance circuits.

(4) Consilience with metallogeny. Independent mining histories outline a Sumatran gold belt compatible with the corridor hypothesis and the Batang Hari axis (e.g., van Leeuwen 2014; 2022). This raises the prior that Ptolemaic “golden” toponyms can include Sumatra-side nodes.

(5) Linguistic echo and metonymy. The Malayic tanjung denotes a projecting landform (marine or fluvial). A famed local tanjung (e.g., Tanjung Emas) can be metonymically elevated to a regional chersonesos in Greek. In parallel, dvīpa in Suvarṇadvīpa is scale-flexible (from island to macro-region). Thus Greek “peninsula” and Indic “island of gold” reflect different scales/vantage points across the same Sumatran-centered corridor (see Table 2 notes).

(6) Itinerary realism. Read geometrically, Ptolemy Book 1, ch. 14 treats the first leg parallel to the equator and the second toward south-and-east (see Greek note). Monsoon-aware sailing reconstructions (Figure 4) naturally touch both shores across seasons; we therefore test Malaya Peninsula-only vs Malaya Peninsula–Sumatra routes by sailing-time residuals.

Implication. The Malay Peninsula mainstream placements remain compatible with a bi-littoral reading; selected toponyms show equal or better Sumatra fits in Table 2 and Tables 3. The corridor model yields testable predictions (archaeometallurgy, toponymy audits, route modeling) rather than a fixed point-location claim.

4.2 Counter-arguments and replies

Etymology (Peninsula vs. Island): Objection: the Greek χερσόνησος (chersonēsos) explicitly means “peninsula,” so an island identification is excluded. Reply: in Ptolemaic usage chersonēsos functions as a typological, macro-regional label—a compiler’s normalization of a coastal zone anchored by salient headlands—rather than a precise geomorphic diagnosis of every node within it. The elasticity is visible in the Greco-Roman dossier itself: “golden” toponyms appear as both promontory and island (e.g., Periplus Maris Erythraei chs. 63–64; Pliny, Natural History 6 [Promunturium Chryse and the Insulas Chrysen et Argyrēn]; Pomponius Mela, Chorographia 3.70; Dionysius Periegetes, Periegesis; Avienus, Ora Maritima). A locally famous tanjung (promontory-like high ground) can thus be metonymically elevated to a regional chersonēsos in Greek. On the Indic side, Suvarṇadvīpa (“island of gold”) is likewise scale-flexible: dvīpa ranges from literal islands to large cultural-geographic units (cf. Jambudvīpa for the Indian subcontinent), and labels such as Suvarṇabhūmi/Suvarṇadvīpa recur in texts and epigraphy (e.g., Mahāvaṃsa; Jātaka; Milinda Pañha; Padang Roco inscription; Nagarakretagama). Read together, the Greek “peninsula” and the Indic “island of gold” reflect different vantage points and scales across the same Sumatran-centered gold corridor, not a contradiction.

Canonical Malaya Peninsula Placements (Mainstream View). Objection: many Ptolemaic names have long-standing Malaya Peninsula identifications—e.g., Tacola → Takua Pa/Takuapa (Phang-nga); Perimulicus → Gulf of Thailand; Sabana → Singapore/Klang; Maleucolon → Malay Point—in classic treatments (Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese; Gerini, Researches on Ptolemy’s Geography of Eastern Asia; McCrindle’s Ptolemy; Stevenson’s trans.). Reply: our model does not displace these; it contextualizes them. We treat Ptolemy’s coastline list as a mixed-granularity gazetteer compiled from pilots’ reports, in which some labels are typological or metonymic. Accordingly, (i) we admit the Malaya Peninsula littoral assignments where they fit; (ii) we test paired candidates where direction/latitude residuals and onomastic/morphological cues are sharper on Sumatra (e.g., tanjung-based promontories, Batang Hari corridor nodes); and (iii) we allow for conflations (a famed cape/emporion naming a wider reach) and equatorial sign flips in transmission. In short, the Malaya Peninsula mainstream placements remain compatible with a bi-littoral model, while selected toponyms may find better or dual fits on Sumatra; the tables (2, 3) make these tests explicit.

Absence of excavated gold-processing sites on the proposed Sumatra promontory. Critics may note the thin archaeometallurgical record along the east-Sumatra estuaries. Reply: in tropical deltaic settings, surface features of gold working (sluice lines, small pits, earthen settling basins) are low-visibility and often erased by avulsion, mangrove accretion, and agriculture; the highest archaeological signal is expected up-basin on stable terraces rather than on the active estuary front. Independent geological/historical syntheses nevertheless document a long-lived Sumatran gold province, e.g., colonial records of at least 14 gold mines (1899–1940) with ~101 t Au produced—dominated by the Lebong Donok/Lebong Tandai district—situated within broader epithermal/orogenic belts that extend into the Batang Hari hinterland. These histories do not “prove” estuarine processing sites, but they raise prior probability that such sites existed and are masked by taphonomy and survey bias.

4.3 Limitations

Four limitations are salient.

(1) Textual–cartographic uncertainty. Ptolemy’s coordinates are copy-derived (via Marinus) with known distortions (prime-meridian choice, scale/shape compression) and scribal sign errors near the equator. Our use of residual table (Table 3) reduces but does not eliminate this noise; we therefore emphasize relative fits (comparative residuals, paired candidates) over absolute placements.

(2) Geomorphic and taphonomic loss. Tropical delta dynamics—rapid sedimentation, avulsion, mangrove accretion, later agriculture and extraction—erase or bury low-visibility gold-working signatures. This biases the surface record toward up-basin stability. We address this by prioritizing subsurface sampling (coring, geophysics), targeting terrace/levee contexts, and running negative-control transects outside the corridor to bound false positives.

(3) Linguistic palimpsest and onomastic drift. The Malay world layers Sanskritic, Malayic, Old Javanese, and local substrates; later Islamic/colonial spellings and folk etymologies confound straight etymologies. Our crosswalk treats names as probabilistic matches—scored on phonology, semantics, geography, and route coherence—and explicitly records dual candidates where ties persist. Definitive resolutions will require collaboration with historical linguists and dated toponym attestations.

(4) Model simplifications in route simulations. Sailing-time reconstructions approximate seasonal winds, currents, hull/sail performance, and unknown stopovers; the Greek narrative (Ptolemy Book 1, ch.) is interpreted geometrically (first leg parallel to the equator; second leg south-and-east), but alternative readings exist in translations. We mitigate by reporting per-leg residuals, running parameter sweeps/sensitivity analyses, and using results to compare Malaya Peninsula-only vs. Malaya Peninsula–Sumatra models rather than to assert exact day-to-mile conversions.

(A further limitation is evidence imbalance: Malaya Peninsula littoral archaeology is generally better published than Sumatra’s. We note this asymmetry and frame our claims as testable predictions to motivate targeted fieldwork.)

5. Testable predictions and future work

(1) Archaeometallurgy (interior–estuary transects; placer workflows).

Objective. Test for placer-gold processing signatures along the Batang Hari corridor from upper–middle confluences (e.g., Tembesi, Sijunjung) to lower-delta levees/relict channels (Muara Sabak; adjacent tanjung promontories ~0–5 m above active floodplain).

Design & methods.

- Remote sensing/terrain: SRTM/photogrammetry/LiDAR (if available) to map linear tailings/berms, abandoned race lines, terrace-edge benches.

- Coring/transects: vibracoring or Russian-auger lines across levees, point bars, abandoned channels (interior→estuary gradient), plus negative-control transects outside the hypothesized corridor.

- Artefact/microresidue survey: hammer-stones, anvils, crushing slabs; micro-quartz abraded flour, soot/ash films; note that smelting slag is uncommon in placer contexts.

- Geochemistry: fines screening for Au–Ag; Hg spikes as amalgamation proxy (pXRF/ICP-MS); SEM–EDS/FTIR on concentrates.

- Targeted geophysics: magnetometry/EM for hearth lenses or burned features.

- Chronology: AMS ^14C (charcoal) and OSL (tailings/levee accretion) to bracket activity phases.

Decision rules (falsifiable).

- Support for the estuary-linked processing prediction if ≥2 independent lines (e.g., Au–Ag fines + micro-abrasion + dated hearth lens) co-occur at lower Batang Hari nodes and yield dates broadly consistent with 1st–3rd c. CE (Ptolemaic horizon) or sustained pre-/protohistoric activity.

- Revision trigger if signatures are absent at estuary nodes but present upstream only (interior-focused beneficiation), or if dating clusters far outside the hypothesized window.

- Outputs. Georeferenced site inventory (interior→estuary), GIS layers for candidate features, analytical microresidue catalogue, and a brief QA/QC note on contamination controls; figure panel summarizing positive/negative transects.

(2) Toponymy audit (paired placements, scored).

Build a bilingual/trilingual gazetteer for Ptolemaic ↔ Malay/Old Javanese/Sanskrit forms on both shores (Batang Hari basin vs. Malaya Peninsula littoral).

- Prioritize hydronyms, promontory names (tanjung), emporia/market towns, and gold-semantic lexemes.

- For each Ptolemaic name, compute a composite score: (i) phonology/orthography match; (ii) morphology/semantics (e.g., “gold,” “cape,” “river”); (iii) |Δφ| (latitude residual, with equator-ambiguity rule near 0°); (iv) route coherence with adjacent names.

- Treat ties ≤0.2° latitude and ≤1 day sailing as dual candidates; record a “winner” only when one candidate clears both thresholds.

- Outputs: updated Table 2 (notes/etymology column expanded) and Table 3 (scores + winners), plus a short appendix on sound correspondences/loan patterns.

(3) Sailing-time modeling (seasonal residuals).

Run eastbound/westbound simulations under NE/SE monsoon windows using simple square-sail polars and coastal tacking constraints.

- Compare two route families: Malaya Peninsula-only vs Malaya Peninsula–Sumatra (with Muara Sabak / Batang Hari stopover).

- Convert reported “days” to distance via Ptolemaic reduction rules (Leg-1 parallel to equator; Leg-2 S+E bearing).

- Report per-leg residuals (simulated vs. Ptolemaic) and a total misfit (median absolute % error).

- Decision rule: Sumatra model is preferred if it reduces total misfit by ≥20% and improves at least two contiguous legs.

- Outputs: revised Figure 4 panels with residual boxes, plus a one-page methods note.

(4) Comparative metallogenesis (ore–river logistics test).

Overlay gold-province belts (epithermal/orogenic districts) with river least-cost paths to export nodes; estimate interior-to-estuary tonnage friction.

- Inputs: ore-belt polygons, SRTM-derived river networks/gradients, navigability classes, portage penalties, and historical mine districts.

- Compute for each basin (e.g., Batang Hari vs. Pahang/Perak) a logistics index: (ore endowment × fluvial efficiency) → predicted export throughput.

- Decision rule: Hypothesis gains support if Batang Hari ranks top-two under ≥2 parameterizations and aligns with high-score toponyms.

- Outputs: a small metallogenic overlay figure (supporting Figure 2) and a table of basin indices to cite in Discussion.

6. Conclusion

Treating Aurea Chersonesus as a scale-normalized, bi-littoral construct reconciles Ptolemy’s χερσόνησος (“peninsula”) with Indic Suvarṇadvīpa (“island of gold”). Our reading of Ptolemy Book 1, ch. 14—first leg parallel to the equator, second leg toward south-and-east—and the Malayic semantics of tanjung (a projecting landform, not necessarily marine) allow a metonymic elevation from a local promontory (e.g., Tanjung Emas) to a regional chersonesos. Quantitatively, the latitude tests and the toponymy crosswalk (Tables 3, 2) show that several names admit equal or better fits on the Sumatra side, especially along the Batang Hari corridor, while leaving canonical Malaya Peninsula littoral placements intact where they remain competitive. Independent metallogenic histories of Sumatra’s gold province further raise the prior for a Sumatra-centered corridor rather than a single peninsular point.

The model is deliberately testable. Three levers can raise or lower its probability: (i) archaeometallurgical survey targeted at terrace/levee nodes from interior to estuary; (ii) toponymy audits that resolve paired/dual placements; and (iii) sailing-time residuals under seasonal winds (Figure 4). At a minimum, the Golden Chersonese should be read as a corridor, not a dot on the map—one in which Sumatra’s Suvarṇadvīpa plays a constitutive role while Malay Peninsula identifications remain part of a bi-littoral solution set.

Acknowledgments

I thank colleagues and readers for helpful comments on earlier drafts. This article draws on datasets developed in the Sundaland research program (2010–present); all interpretations and any errors are my own.

Funding

No external funding was received. The research was undertaken within the Sundaland research program.

Data availability

All tabular data are provided in Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3. Working spreadsheets and figure files are available from the author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

References

Avienus, Rufus Festus. 1934. Ora Maritima. Ed. A. Berthelot. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

Bennett, Anna T. N. 2009. “Gold in Early Southeast Asia.” ArchéoSciences 33: 99–107. https://doi.org/10.4000/archeosciences.2072.

Dionysius Periegetes. 2014. Dionysius Periegetes: Description of the Known World. Ed., trans., and comm. J. L. Lightfoot. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gerini, G. E. 1909. Researches on Ptolemy’s Geography of Eastern Asia (Further India and Indo-Malay Archipelago). London: Royal Asiatic Society & Royal Geographical Society.

Irwanto, Dhani. 2017 “Article on Aurea Chersonesus.” AtlantisJavaSea.com. Retreived from https://atlantisjavasea.com/2017/06/08/aurea-chersonesus-is-in-sumatera/

Irwanto, Dhani. 2019 Sundaland: Tracing the Cradle of Civilizations. Bogor: Indonesia Hydro Media. ISBN: 9786027244924. (includes section on Aurea Chersonesus)

Josephus, Flavius. 1930–1965. Jewish Antiquities. Trans. H. St. J. Thackeray et al. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (See esp. Vol. I, 1930.)

Jātaka: Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births. 1895–1907. 6 vols. Trans. R. Chalmers, W. H. D. Rouse, H. T. Francis, and E. B. Cowell (ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (for the Pali Text Society; reprinted PTS, 1990).

Linehan, W. 1951. “The Identifications of Some of Ptolemy’s Place-Names in the Golden Khersonese.” Journal of the Malaya Peninsulan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 24 (3): 1–24.

Mahāvaṃsa. 1912. The Mahāvaṃsa or The Great Chronicle of Ceylon. Trans. Wilhelm Geiger. London: Published for the Pali Text Society by Oxford University Press.

Milinda Pañha (The Questions of King Milinda). 1890–1894. 2 vols. Trans. T. W. Rhys Davids. Sacred Books of the East 35–36. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Padang Roco (Amoghapāśa) Inscription. 1286 CE. For text, discussion, and translations see: Krom 1916; Moens 1924; Slamet Muljana 1981; and later syntheses.

Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. 1989. The Periplus Maris Erythraei: Text with Introduction, Translation, and Commentary. Trans. Lionel Casson. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pliny the Elder. 1942. Natural History, Vol. II: Books 3–7. Trans. H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library 352. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ptolemaeus, Claudius. 1843–1845. Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia. Ed. C. F. A. Nobbe. Leipzig: B. G. Teubner (repr. Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1966).

Ptolemaeus, Claudius. 1932. The Geography of Claudius Ptolemy. Trans. and ed. Edward Luther Stevenson; intro. Joseph Fischer. New York: New York Public Library (repr. Dover, 1991).

Ptolemaios, Klaudios. 2006. Handbuch der Geographie. Griechisch–Deutsch. Eds. Alfred Stückelberger and Gerd Graßhoff. 2 vols. Basel: Schwabe.

van der Meulen, W. J. 1974. “Suvarṇadvīpa and the Chrysê Chersonêsos.” Indonesia 18 (October): 1–40.

van Leeuwen, T. M. 2014. “A Brief History of Mineral Exploration and Mining in Sumatra.” In Proceedings of Sundaland Resources 2014 – MGEI Annual Convention (Palembang, 17–18 Nov). https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.2278.5607.

Wheatley, Paul. 1961. The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malaya Peninsula before A.D. 1500. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Peninsula Press. Repr. 1973, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

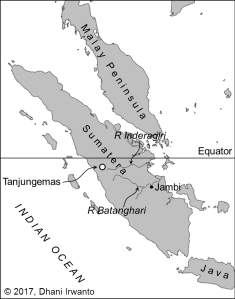

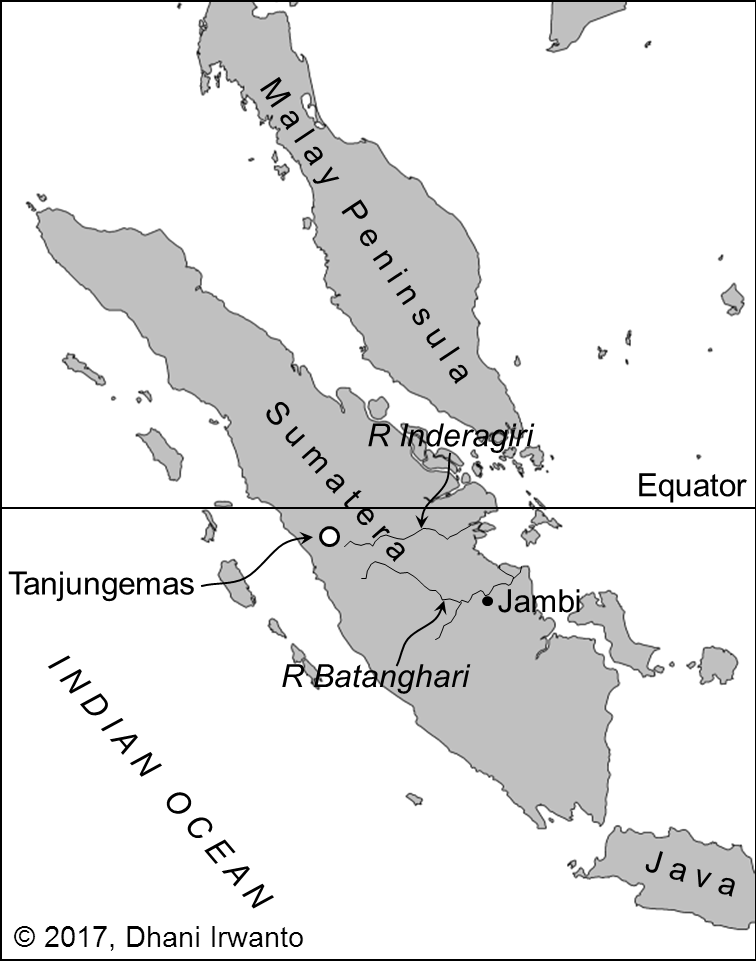

Figure 1. Regional map of the Malaya Peninsula–Sumatra bi-littoral “Golden Corridor”.

Figure 2. Distribution of mineral occurrences, prospects and deposits in Sumatra (van Leeuwen and Pieters, 2014). Location of Tanjung Emas is added.

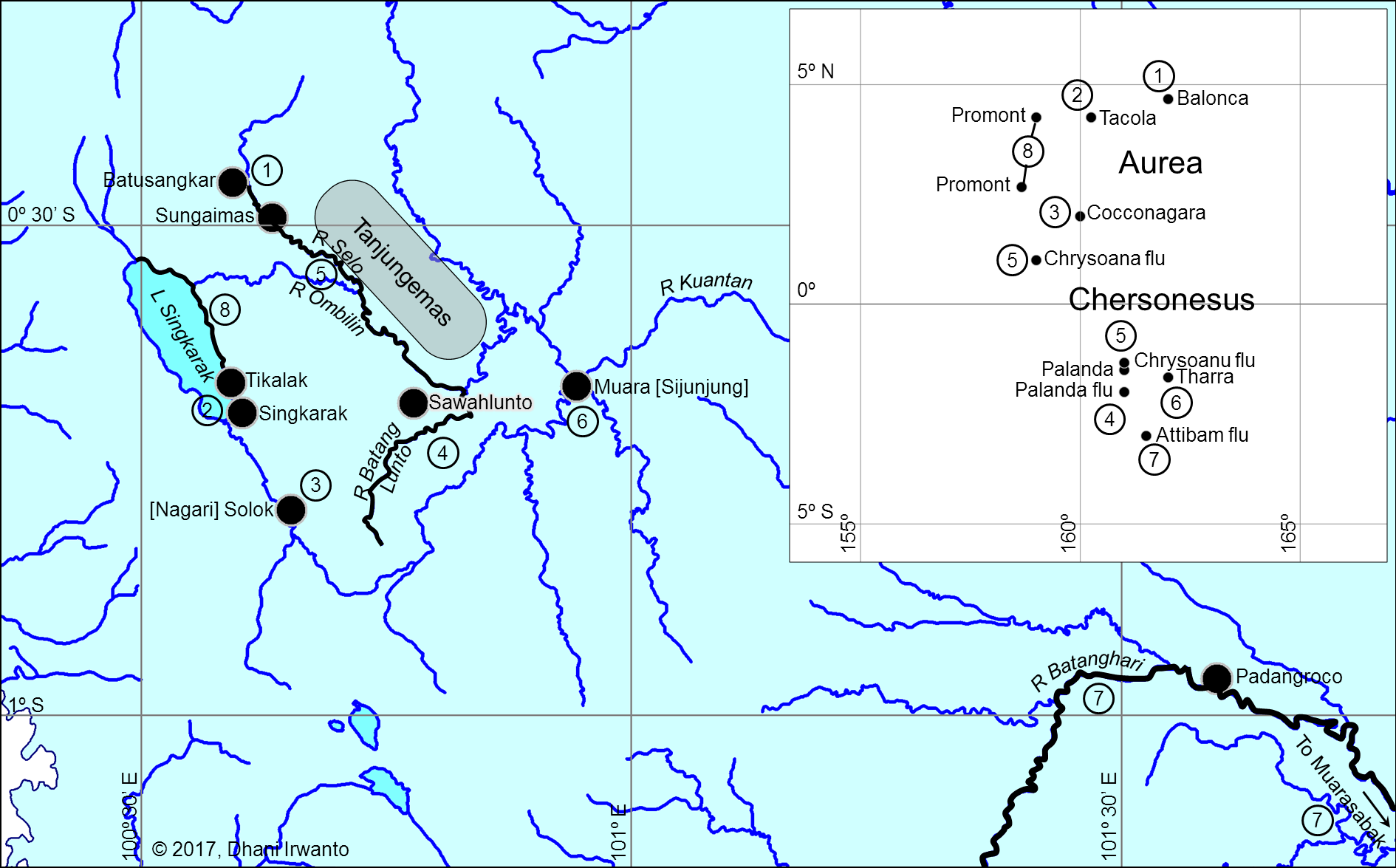

Figure 3A. Reconstruction of Ptolemy’s coordinates and identified toponymy for area of Golden Chersonese (Irwanto, 2017).

Inset is the plot of places given by Ptolemy with his coordinate system. Numbers are related to the explanations in the text.

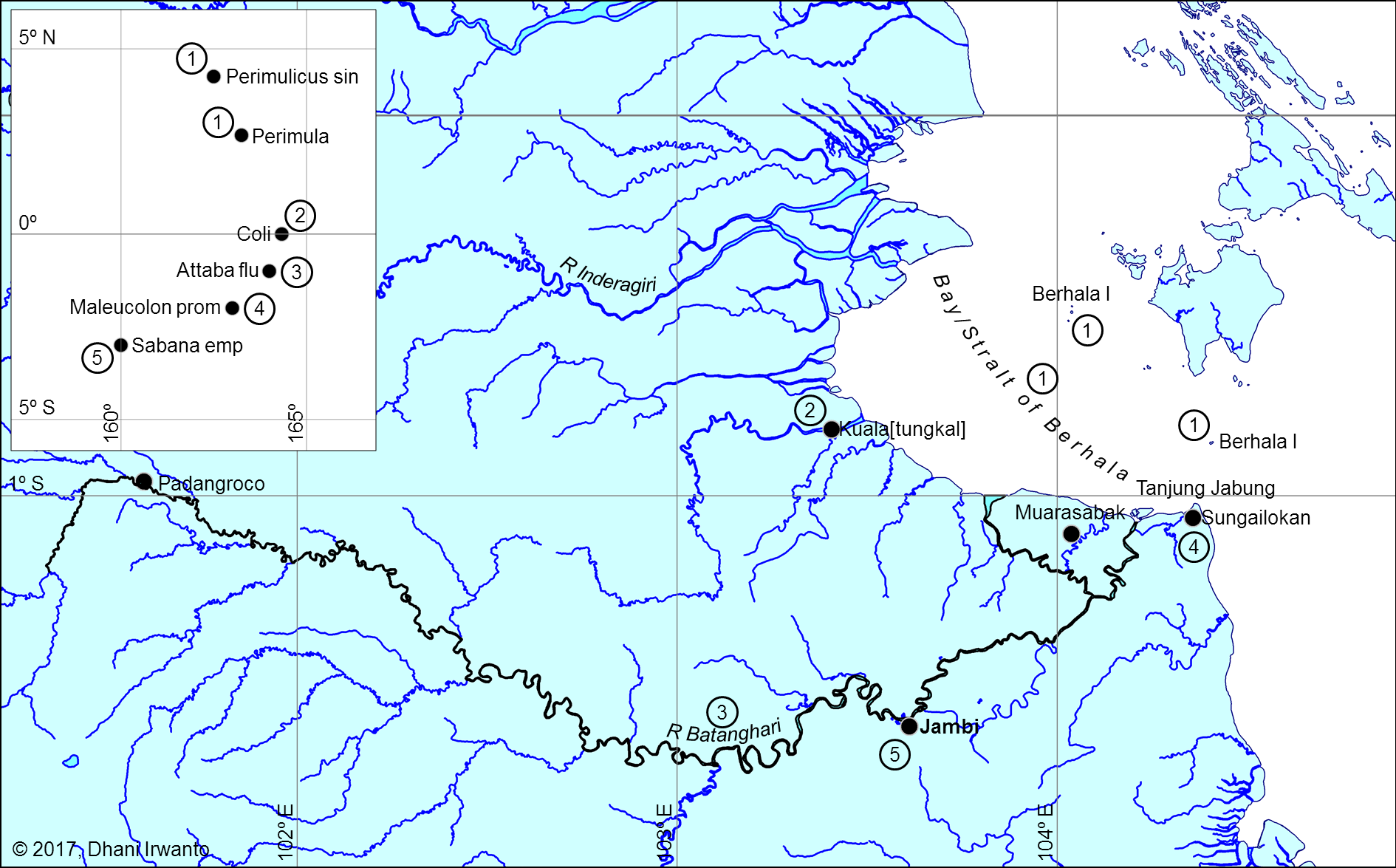

Figure 3B. Reconstruction of Ptolemy’s coordinates and identified toponymy for area of eastern coast (Irwanto, 2017).

Inset is the plot of places given by Ptolemy with his coordinate system. Numbers are related to the explanations in the text.

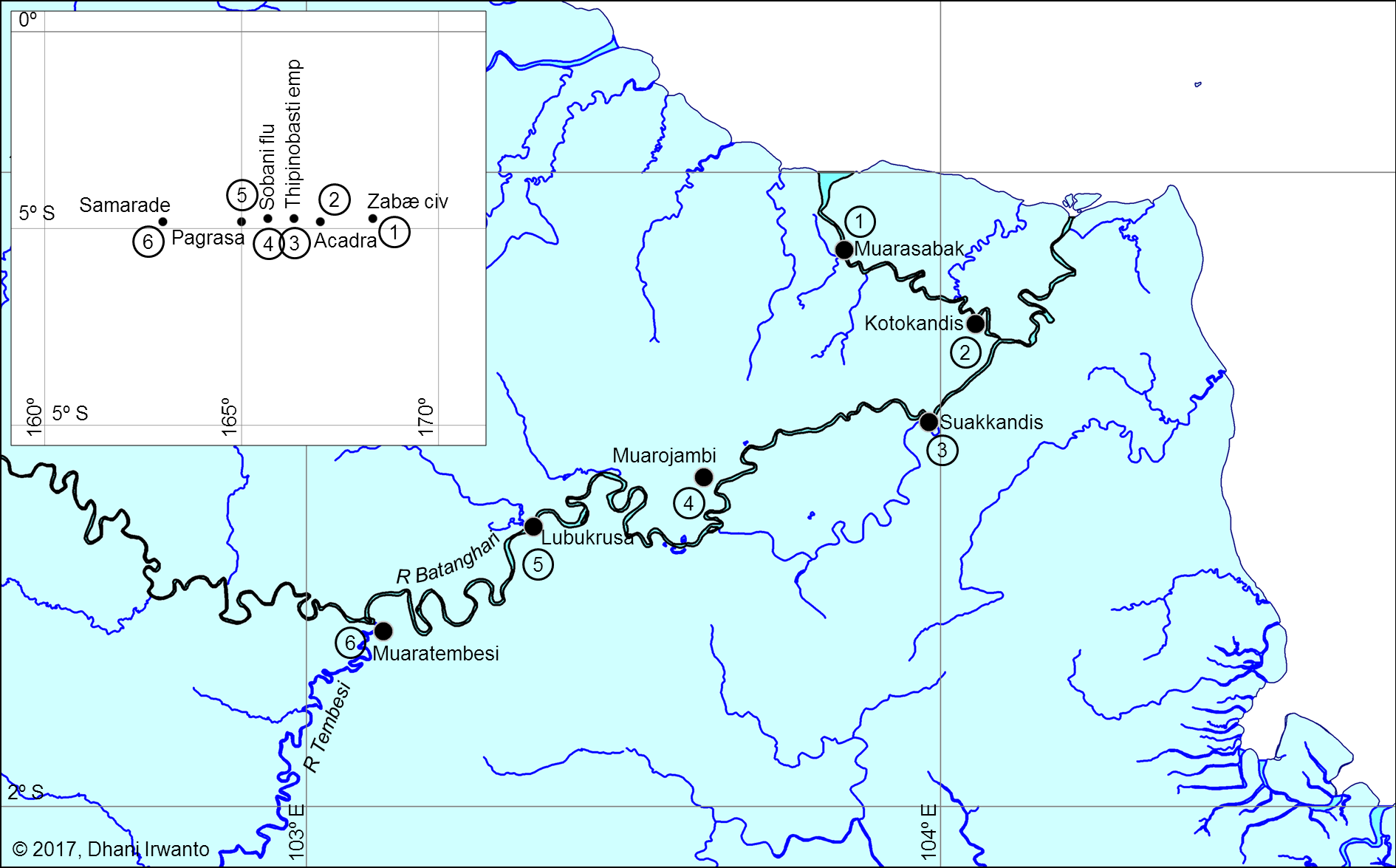

Figure 3C. Reconstruction of Ptolemy’s coordinates and identified toponymy for area of piracy prone (Irwanto, 2017).

Inset is the plot of places given by Ptolemy with his coordinate system. Numbers are related to the explanations in the text.

Figure 4A. Monsoon routing schematic with sailing-time residuals (Malay Peninsula-only vs Malay Peninsula–Sumatra models) — residuals from observed rutters (Δt, days).

Figure 4B. Monsoon routing schematic with sailing-time residuals (Malay Peninsula-only vs Malay Peninsula–Sumatra models) — A/B/C segmentation (modeled at 4 kn; Δt for C only).

Table 1. Gazetteer and GIS coordinates (Batanghari corridor).

| Ptolemaic Form | Feature Type | Modern Name | Longitude | Latitude |

| Aurea Chersonesus | promontory | Tanjung Emas (“Golden Promontory”) | 100.762972 | -0.438524 |

| Balonca | place | Batu Sangkar | 100.593900 | -0.456900 |

| Tacola | emporium (trading place) | Tikalak, Singkarak | 100.597700 | -0.676600 |

| Cocconagara | place | Nagari Solok | 100.653100 | -0.791100 |

| Palanda | fluvius (river) | Batang Lunto | 100.800529 | -0.706759 |

| Palanda | place | Sawah Lunto | 100.778400 | -0.682000 |

| Chrysoana/Chrysoanu | fluvius (river) | Sungai Mas (‘gold river’), Selo River and upper Ombilin River | 100.634200 | -0.492800 |

| Tharra | place | Muara (Muara Sijunjung) | 100.944600 | -0.664700 |

| Attibam | fluvius (river) | Upper Batang Hari River | 101.597545 | -0.963209 |

| Promontorium | promontory | Several places named with “Tanjung” (“promontory”) at coast of Lake Singkarak | 100.566780 | -0.598574 |

| Perimula | place | Berhala Island | 104.040085 | -0.516267 |

| Perimulicus | sinus (bay) | Bay/Strait of Berhala | 103.933170 | -0.667159 |

| Coli | civitas (social body of citizens) | Several places named with “Kuala” (“estuary” [of small rivers]) at eastern coast | 103.594618 | -0.932387 |

| Coli | civitas (social body of citizens) | Kuala Tungkal | 103.406822 | -0.825672 |

| Attaba | fluvius (river) | Batang Hari River (previously Batang Sabak River) | 103.720431 | -1.434334 |

| Maleucolon | promontory | Sungai Lokan (village), Tanjung Jabung (promontory) | 104.357700 | -1.059200 |

| Sabana | emporium (trading place) | Jambi city | 103.611100 | -1.607200 |

| Zabæ | civitas (social body of citizens) | Muara Sabak (a village at estuary (‘muara’) of Sabak/Batang Hari River) | 104.037921 | -1.101304 |

| Sarabes | estuary | Muara (estuary of) Sabak (river) | 103.848494 | -1.122666 |

| Acadra | place | Koto Kandis | 104.055669 | -1.239440 |

| Thipinobasti | emporium (trading place) | Suak Kandis | 103.982107 | -1.394223 |

| Sobani | fluvius (river) | Lesser Jambi Stream, Muaro Jambi | 103.626978 | -1.481124 |

| Pagrasa | place | Lubuk Rusa | 103.359029 | -1.561840 |

| Samarade | place | Muara Tembesi | 103.121965 | -1.723715 |

| Deltaic channel/ Settlement | Nipah Panjang | 104.207044 | -1.071452 | |

| Delta channel/River | Mendahara River | 103.915658 | -1.143107 |

Table 2. Toponymy crosswalk (Malaya Peninsula mainstream vs. Sumatra candidates).

| Ptolemaic form | Category | Malaya Peninsula littoral (mainstream view) | Sumatra candidate (this study) |

| Aurea Chersonesus | promontory | Malaya Peninsula | Tanjung Emas[1] |

| Balonca | place | Uncertain/not attested | Batu Sangkar |

| Tacola | emporium (trading place) | Takua Pa/Phang Nga; (alt. Kedah) | Tikalak, Singkarak |

| Cocconagara | place | Uncertain/not attested | Nagari Solok |

| Palanda | fluvius (river) | Johor River | Batang Lunto |

| Palanda | place | Kota Tinggi | Sawah Lunto |

| Chrysoana/Chrysoanu | fluvius (river) | Perak/Bernam sector (river of gold) | Sungai Mas (‘gold river’), Selo River and upper Ombilin River |

| Tharra | place | Uncertain/not attested | Muara (Muara Sijunjung) |

| Attibam | fluvius (river) | Upper Pahang system | Upper Batang Hari River |

| Promontorium | promontory | Uncertain/not attested | Several places named with “Tanjung” (“promontory”) at coast of Lake Singkarak |

| Perimula | place | NE coast; Ligor/Kelantan/ Terengganu (uncertain) | Berhala Island |

| Perimulicus | sinus (bay) | Gulf of Thailand | Bay/Strait of Berhala |

| Coli | civitas (social body of citizens) | Kole polis: Kelantan– Kuantan sector | Several places named with “Kuala” (“estuary” [of small rivers]) at eastern coast |

| Attaba | fluvius (river) | Pahang River (alt. Terengganu) | Batang Hari River (previously Batang Sabak River) |

| Maleucolon | promontory | Malay Point, SE coast (Johor–Pahang) | Sungai Lokan (village), Tanjung Jabung (promontory) |

| Sabana | emporium (trading place) | Southern tip emporion: Singapore or Klang (uncertain) | Jambi city |

| Zabæ[2] | civitas (social body of citizens) | Uncertain placement | Muara Sabak (a village at estuary (‘muara’) of Sabak/Batang Hari River) |

| Sarabes | estuary | Uncertain placement | Muara (estuary of) Sabak (river) |

| Acadra | place | Hà Tiên (Gulf of Thailand) | Koto Kandis |

| Thipinobasti | emporium (trading place) | Hà Tiên sector | Suak Kandis |

| Sobani | fluvius (river) | Uncertain/not attested | Lesser Jambi Stream, Muaro Jambi |

| Pagrasa | place | Uncertain/not attested | Lubuk Rusa |

| Samarade | place | Uncertain/not attested | Muara Tembesi |

| Deltaic channel/ Settlement | nan | Uncertain/not attested | Nipah Panjang |

| Delta channel/River | nan | Uncertain/not attested | Mendahara River |

Note on McCrindle’s “coast facing south” (Ptolemy, Geog. 1.14)

A widely quoted English rendering by McCrindle reads: “since as the coast faces the south it must run parallel with the equator … ‘we must reduce … from Zabæ to Kattigara, since the course of the navigation is towards the south and the east.’”

The underlying Greek makes a geometric point about coastline orientation, not a southbound course on the first leg. Ptolemy says the Golden Chersonese → Zabæ stretch is “παράλληλον οὖσαν τῷ ἰσημερινῷ” (“parallel to the equator”), and explains that the intervening region runs opposite to the south—i.e., it trends east–west—so no angular reduction is needed. By contrast, the Zabæ → Cattigara leg is explicitly a sailing bearing: “τὸ τὸν πλοῦν εἶναι πρὸς νότον καὶ πρὸς ἀνατολάς” (“the voyage is toward the south and toward the east”), which is why that leg is reduced.

Implication. Translating the first clause as “the coast faces south” risks a syntagmatic slippage: it treats a statement about coastal aspect (used to justify an E–W treatment) as if it were the ship’s heading. Read with the Greek geometry in view, Ptolemy’s two-step logic is: (1) GC → Zabæ runs parallel to the equator (no reduction), then (2) Zabæ → Cattigara runs SE (reduce to the E–W component).

[1] Local usage of tanjung denotes a projecting landform in marine, lacustrine, or fluvial settings; here Tanjung Emas is a higher patch protruding into a lower floodplain along the Batanghari, not necessarily a marine tanjung. Metonymy: a prominent tanjung can label its surrounding littoral; Ptolemy’s chersonesos may reflect such upscaling.

[2] Greek text (Ptolemy Book I): Τὴν μὲν οὖν ἀπὸ τῆς Χρυσῆς Χερσονήσου ἐπὶ Ζάβας οὐδέν τι δεῖ μειοῦν, παράλληλον οὖσαν τῷ ἰσημερινῷ, διὰ τὸ τὴν μεταξὺ χώραν ἀντίαν ἐκτετάσθαι τῇ μεσημβρίᾳ. [Lit.] “There is no need to reduce the [distance] from the Golden Chersonese to Zabæ, (it) being parallel to the equator, because the region between extends opposite to the south (i.e., trending east–west).” τὴν δ᾽ ἀπὸ Ζαβῶν ἐπὶ τὰ Καττίγαρα προσήκει συνελεῖν διὰ τὸ τὸν πλοῦν εἶναι πρὸς νότον καὶ πρὸς ἀνατολάς. [Lit.] “But the (distance) from Zabæ to Cattigara must be shortened, because the voyage is towards the south and towards the east.”

Table 3. Ptolemy vs Sumatra and Malaya Peninsula placements (|Δφ|)

| Ptolemaic form | Ptolemy lat (reported) (deg) | Sumatra candidate (modern) | Sumatra lat (deg) | Sumatra |Δφ| (deg) | Malaya lat (deg) | Malaya |Δφ| (deg) |

| Acadra | -4.833 | Koto Kandis | -1.239 | 3.594 | 10.380 | 15.213 |

| Attaba | -1.000 | Batang Hari River | -1.434 | 0.434 | 3.530 | 4.530 |

| Attibam | -3.000 | Upper Batang Hari River | -0.963 | 2.037 | 3.800 | 6.800 |

| Balonca | 4.667 | Batu Sangkar | -0.457 | 5.124 | ||

| Chrysoana/ Chrysoanu | 1.000 | Sungai Mas, Selo River and upper Ombilin River | -0.493 | 1.493 | 4.020 | 3.020 |

| Chrysoana/ Chrysoanu | -1.333 | Sungai Mas, Selo River and upper Ombilin River | -0.493 | 0.840 | 4.020 | 5.353 |

| Cocconagara | 2.000 | Nagari Solok | -0.791 | 2.791 | ||

| Coli | 0.000 | Several places named with “Kuala” at eastern coast | -0.932 | 0.932 | 6.150 | 6.150 |

| Maleucolon | -2.000 | Sungai Lokan Tanjung Jabung | -1.059 | 0.941 | 2.500 | 4.500 |

| Pagrasa | -4.833 | Lubuk Rusa | -1.562 | 3.271 | ||

| Palanda | -1.500 | Batang Lunto | -0.707 | 0.793 | 1.730 | 3.230 |

| Palanda | -2.000 | Sawah Lunto | -0.707 | 1.293 | 1.420 | 3.420 |

| Perimula | 2.667 | Berhala Island | -0.516 | 3.183 | 8.430 | 5.763 |

| Perimulicus | 4.250 | Bay/Strait of Berhala | -0.667 | 4.917 | 10.000 | 5.750 |

| Promontori-um | 2.667 | Several places named with “Tanjung” at coast of Lake Singkarak | -0.599 | 3.265 | 2.500 | 0.167 |

| Promontori-um | 4.250 | Several places named with “Tanjung” at coast of Lake Singkarak | -0.599 | 4.849 | 2.500 | 1.750 |

| Sabana | -3.000 | Jambi city | -1.607 | 1.393 | 1.290 | 4.290 |

| Samarade | -4.833 | Muara Tembesi | -1.724 | 3.110 | ||

| Sobani | -4.750 | Lesser Jambi Stream, Muaro Jambi | -1.481 | 3.269 | ||

| Tacola | 4.250 | Tikalak, Singkarak | -0.677 | 4.927 | 8.850 | 4.600 |

| Tharra | -1.667 | Muara (Muara Sijunjung) | -0.665 | 1.002 | ||

| Thipinobasti | -4.750 | Suak Kandis | -1.394 | 3.356 | 10.380 | 15.130 |

| Zabæ | -4.750 | Muara Sabak | -1.101 | 3.649 | ||

| Mean | -0.804 | -0.967 | 2.625 | 5.087 | 5.587 |