A research by Dhani Irwanto, 19 August 2025

Abstract

This paper proposes a comprehensive analytical framework for historical reconstruction (Renfrew & Bahn, 2016) through semiotic and linguistic decoding. Rather than beginning from archaeological artifacts alone, the framework treats myths, legends, and ancient texts as structured sign systems that preserve fragments of historical memory. Building on Saussure’s dyadic model (Saussure, 1983), Peirce’s triadic model (Peirce, 1931–1958), Jakobson’s syntagmatic-paradigmatic relations (Jakobson, 1960), and Barthes’ orders of signification (Barthes, 1964, 1972), the approach decodes narratives to uncover archetypal structures and latent historical references. The approach further combines semiotic and linguistic decoding with the principle of consilience, where converging evidence from diverse domains enhances reliability in historical reconstruction. Reconstruction is guided by three interpretive models—potsherds, anastylosis, and puzzle—supported by the convergence of independent evidence across disciplines. The framework is then applied in case studies, including Sundaland (Irwanto, 2019), Atlantis (Irwanto, 2015, 2016), the Land of Punt (Irwanto, 2015, 2019), Taprobana (Irwanto, 2015, 2019), and Aurea Chersonensus (Irwanto, 2017, 2019), to demonstrate its explanatory power. The paper ultimately argues for semiotics (Chandler, 2007) and consilience as rigorous tools for bridging the gap between myth and history.

1. Introduction

Reconstructing ancient history often requires working with incomplete, ambiguous, or symbolically encoded sources. Archaeological remains, oral traditions, and written legends all carry traces of the past, but they are mediated by cultural transformations, mythologization, and temporal distance. Traditional historiography has often dismissed such sources as unreliable. However, semiotics—the study of signs and signification—offers a methodological pathway for decoding these symbolic materials and reassembling them into plausible historical narratives.

This paper develops an interdisciplinary framework for such reconstruction, combining semiotic theory, linguistics, and comparative analysis with supporting evidence from archaeology, genetics, climatology, and cartography. Central to this framework is the idea that myths and legends function as signs operating on multiple levels: literal denotation, cultural connotation, and collective myth. By decoding these levels systematically, one can extract enduring archetypes that point toward historical realities.

The aim of the paper is not merely to revisit legendary civilizations, but to establish a replicable analytical framework for transforming symbolic narratives into structured historical hypotheses. The subsequent sections lay out the theoretical underpinnings, methodological tools, and applications of this framework, before concluding with a discussion of its broader implications for the study of ancient civilizations.

2. Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework guiding this research is grounded in semiotic analysis and linguistic decoding, enriched by insights from archaeology, epigraphy, and comparative history. The objective is to establish a structured and interdisciplinary foundation for reconstructing historical realities from fragmented, symbolic, and textual evidence.

2.1 Semiotic Foundations

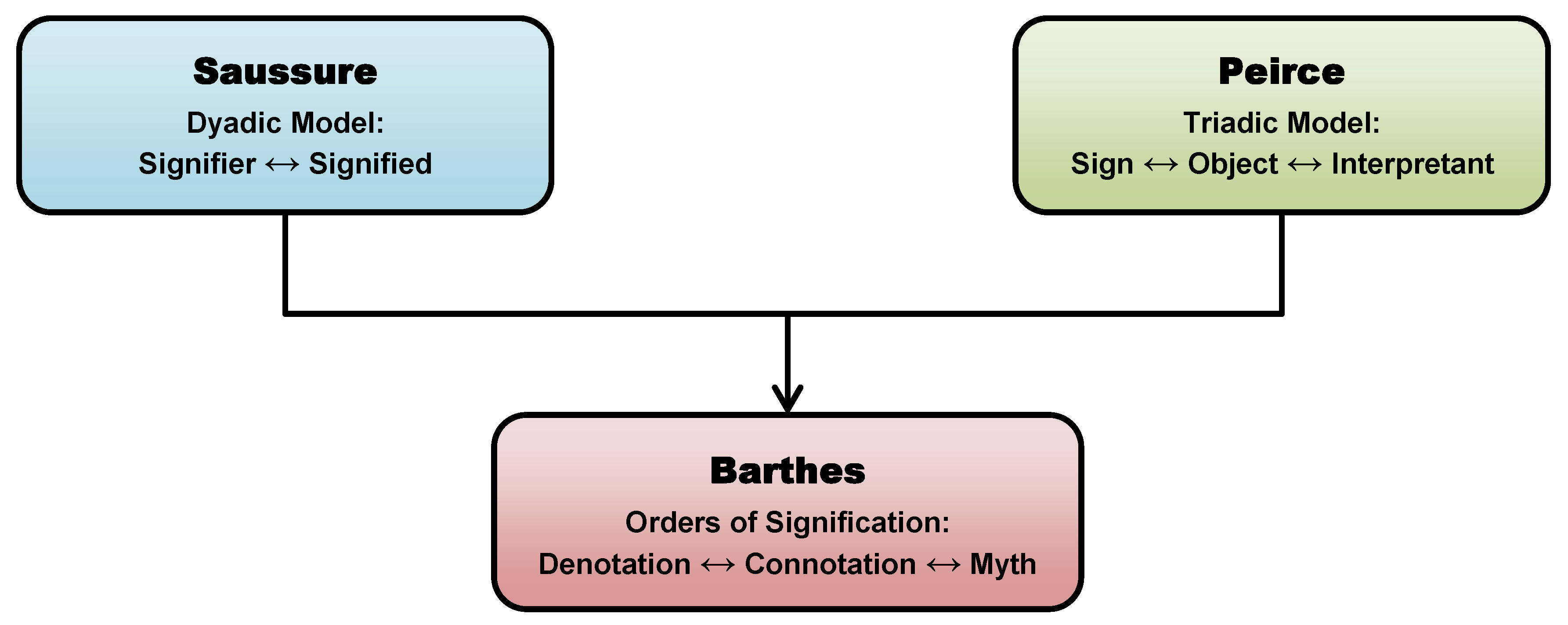

At its core, semiotics provides a methodology for interpreting signs and symbols (Chandler, 2007). Following Ferdinand de Saussure, the relationship between signifier (form) and signified (concept) is recognized as fundamental (Saussure, 1983). Charles Sanders Peirce further refines this by distinguishing icons, indices, and symbols as categories of signs (Peirce; 1931–1958). Roman Jakobson emphasizes communication functions, bridging linguistic and cultural analyses (Jakobson, 1960).

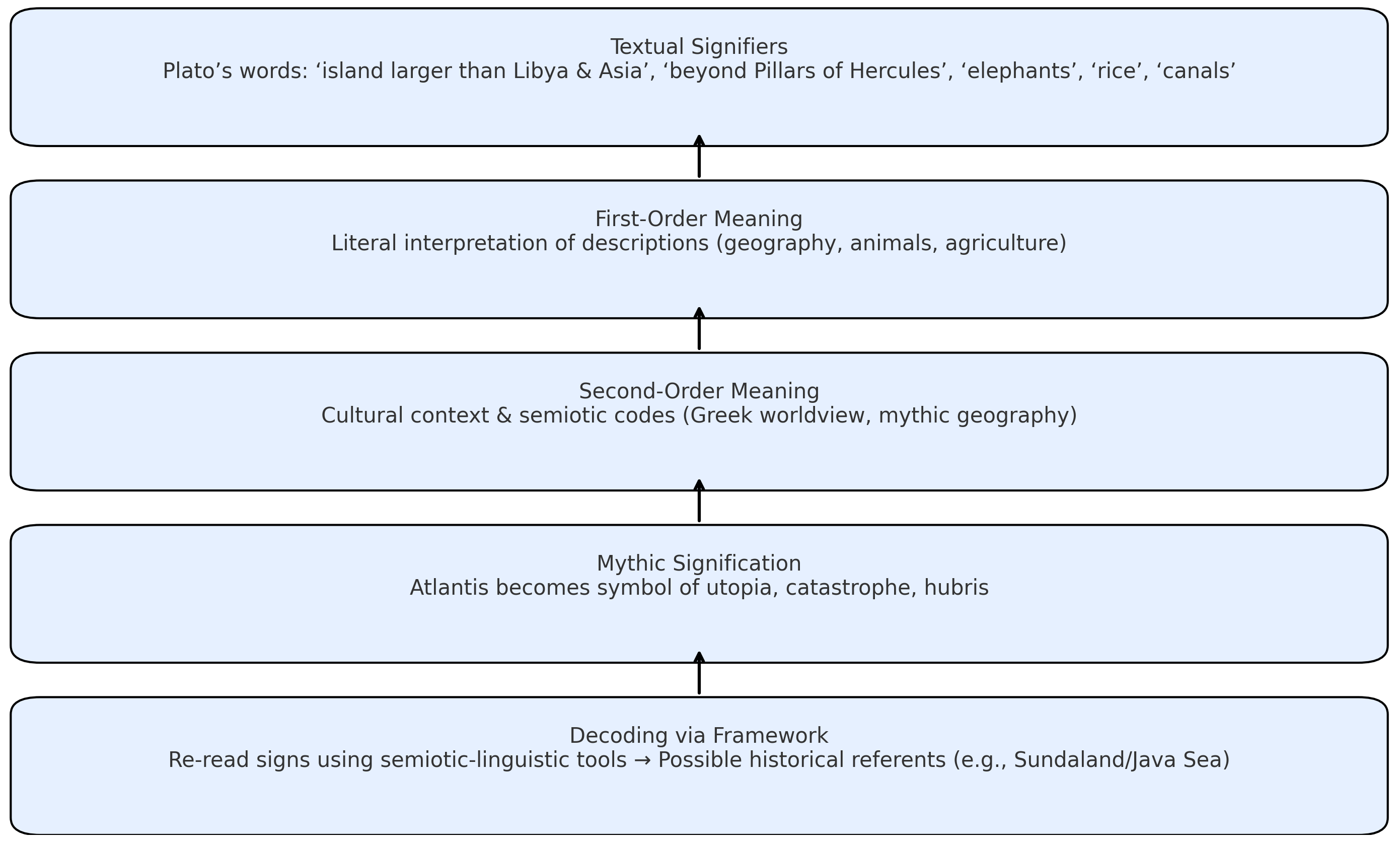

2.2 Barthesian Orders of Signification

Roland Barthes expands semiotic inquiry through his model of successive orders of signification (Barthes, 1964, 1972). The first order, denotation, involves the literal meaning of a sign. The second order, connotation, captures the cultural, emotional, and symbolic associations layered onto the denotative meaning. The third order, myth, encapsulates broader ideological constructs, embedding cultural narratives within semiotic systems. These three levels enable the decoding of texts, artifacts, and inscriptions beyond their surface meaning, thereby revealing the worldviews of past civilizations.

2.3 Models of Historical Reconstruction

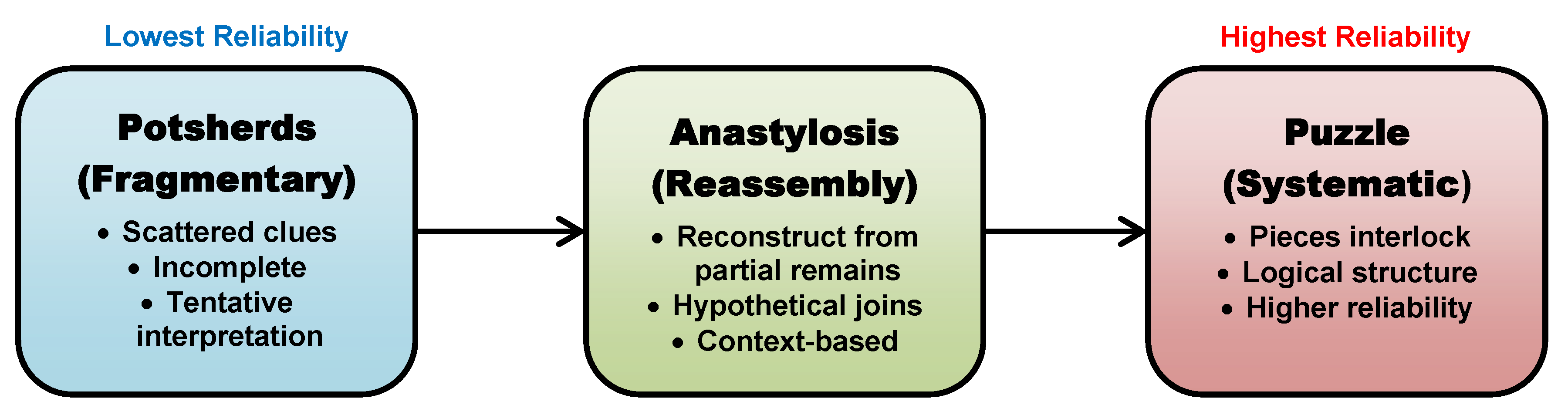

The act of reconstruction in historical research requires methodological models to bridge fragmentary evidence with coherent interpretation. Three conceptual models guide this work:

- Potsherds Model – Each fragment of evidence (a text, symbol, artifact, or inscription) is treated as an isolated piece of a larger whole. Through comparative analysis, connections between fragments are drawn, gradually reconstructing the broader cultural or historical reality.

- Anastylosis Model – Borrowed from architectural reconstruction, this approach uses surviving original elements to reassemble the most plausible original structure. In the semiotic framework, authentic inscriptions, texts, and symbols serve as anchors, while missing parts are inferred cautiously from parallels.

- Puzzle Model – This emphasizes the holistic assembly of disparate parts, often from different contexts. Here, the researcher arranges multiple forms of evidence (linguistic, symbolic, archaeological) into a coherent narrative, even if not all pieces are available. The emphasis is on coherence and plausibility rather than completeness.

Figure 1. Conceptual diagram of the three models (Potsherds, Anastylosis, Puzzle)

2.4 Integrative Analytical Framework

By integrating the semiotic traditions of Saussure, Peirce, Jakobson, and Barthes with the reconstruction models, this framework provides both theoretical and practical tools. Semiotics decodes the layers of meaning, while the reconstruction models guide the methodological assembly of fragmented data into historically grounded interpretations.

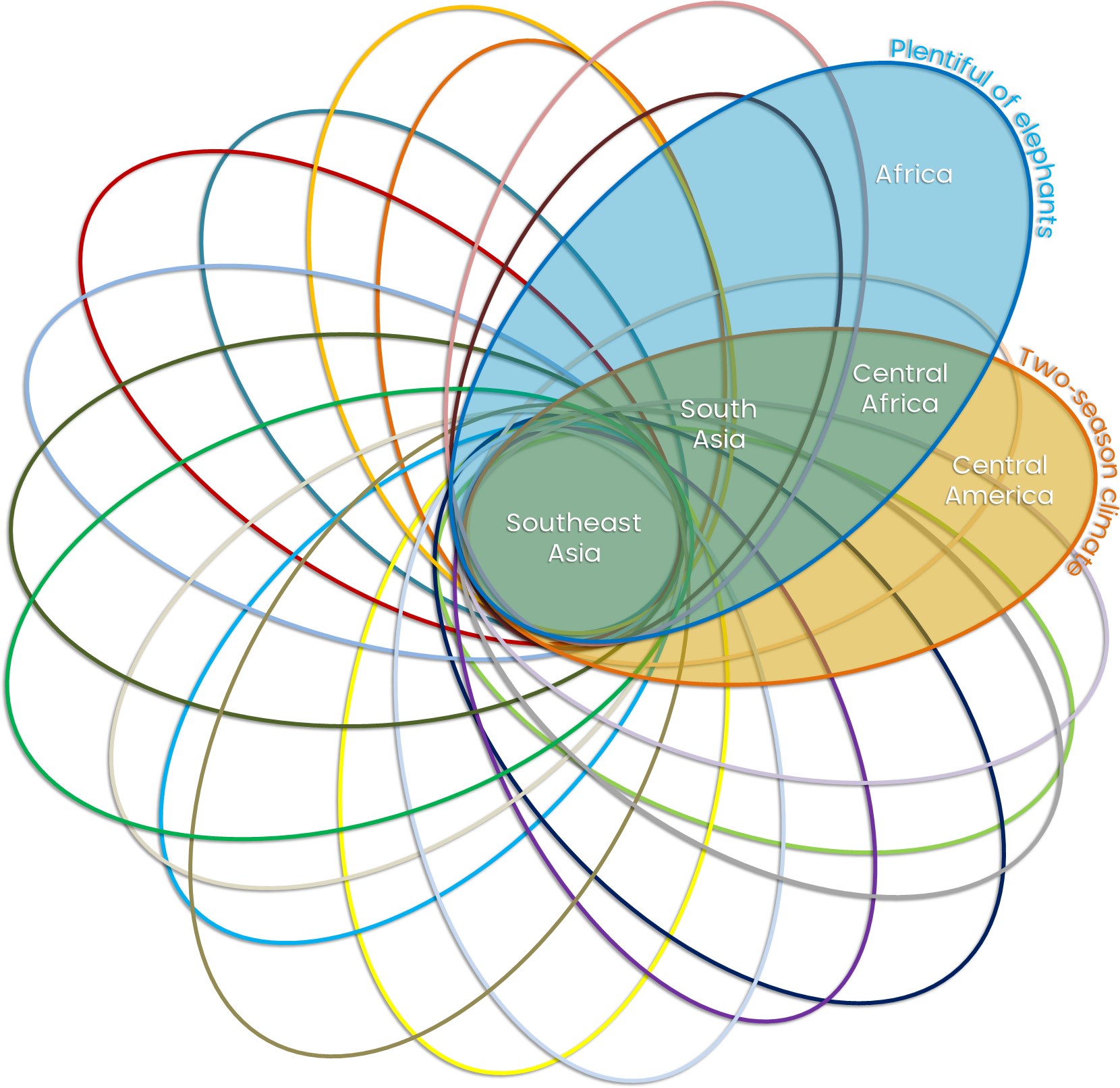

2.5 Consilience of Evidence

The framework adopts the principle of consilience, originally articulated by William Whewell (1840) and later elaborated by Edward O. Wilson (1998). Consilience denotes the independent convergence of multiple lines of evidence toward the same conclusion. In historical reconstruction, this ensures that semiotic interpretations are corroborated by archaeological, linguistic, geographic, and environmental data, thereby minimizing subjectivity and reinforcing validity. When myths, inscriptions, and artifacts independently align with linguistic and geographical evidence, the resulting reconstruction gains explanatory robustness that surpasses single-disciplinary approaches.

3. Methodology

The methodological framework developed in this study is designed to operationalize semiotic and linguistic decoding as tools for historical reconstruction. The approach integrates multiple layers of evidence—linguistic, archaeological, textual, and symbolic—through a structured sequence of analytical steps. By employing comparative semiotics, interdisciplinary synthesis, and reconstruction models, the methodology ensures both analytical rigor and interpretive flexibility.

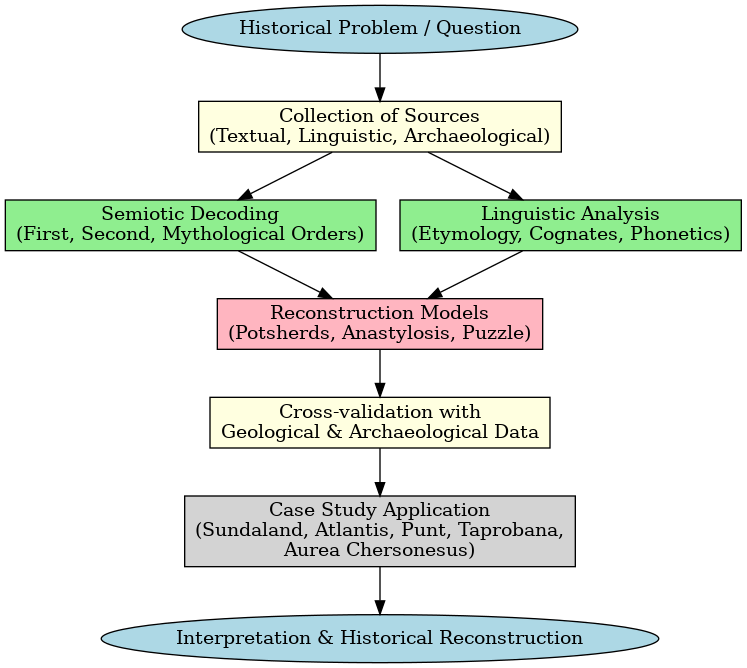

3.1 Workflow Overview

The methodological process can be summarized in a staged workflow that progresses from data collection to reconstruction. This is visualized in a flowchart (Figure 2). The key stages are as follows:

- Collection of primary sources: legends, ancient texts, inscriptions, archaeological artifacts, and symbolic records.

- Semiotic decoding using Peircean triadic analysis (Peirce, 1931–1958), Saussurean dyadic model (Saussure, 1983), and Jakobsonian functions of language (Jakobson, 1960).

- Application of Barthesian orders of signification (denotation, connotation, myth) to uncover cultural layers of meaning (Barthes, 1964, 1972).

- Cross-validation with archaeological, linguistic, and ethnographic evidence.

- Reconstruction using models: Potsherds (fragmentary evidence), Anastylosis (partial restoration), and Puzzle (synthesis of dispersed data).

- Evaluation and iterative refinement based on triangulation of evidence.

At each stage, the principle of consilience is applied as a validation step: semiotic interpretations and linguistic decodings are tested against independent evidence from archaeology, geography, climatology, and cultural studies. Only when multiple sources converge toward the same conclusion is the reconstruction advanced as robust.

Figure 2. Methodological workflow flowchart

3.2 Semiotic-Linguistic Integration

At the core of the methodology lies the integration of semiotics and linguistics. Semiotics (Chandler, 2007) provides the interpretative lens for decoding symbolic structures, while linguistics offers the analytical tools to assess textual and oral traditions. By applying multiple semiotic frameworks, the methodology avoids reliance on a single interpretative model and instead fosters triangulated interpretations.

Table 1: Comparative application of semiotic frameworks

| Framework | Core Concept | Analytical Focus | Application in Historical Reconstruction |

| Saussure’s Dyadic Model | Sign = Signifier (form) + Signified (concept) | Binary relationship of linguistic signs | Decoding textual/linguistic units in myths and inscriptions |

| Peirce’s Triadic Model | Sign = Representamen + Object + Interpretant | Process of semiosis through interpretation | Interpreting symbolic structures in myths, artifacts, and geography |

| Jakobson’s Communication Functions | Six functions of language: referential, emotive, conative, phatic, metalingual, poetic | Role of language in communication and meaning-making | Analyzing how narratives function in communication and collective memory |

| Barthes’ Orders of Signification | Three levels of meaning: Denotation (literal), Connotation (cultural), Myth (ideological) | Cultural codes, symbolism, and ideology embedded in texts | Revealing hidden cultural and ideological meanings in myths and legends |

Figure 3. Conceptual framework of semiotic orders integrating Saussure’s dyadic, Peirce’s triadic, and Barthes’ layered model of signification

3.3 Reconstruction Models

Reconstruction is undertaken through three complementary models:

- Potsherds Model: Focuses on fragmentary data and interprets them as isolated but meaningful units of cultural expression.

- Anastylosis Model: Seeks to restore broader structures using available fragments while acknowledging gaps and uncertainties.

- Puzzle Model: Integrates dispersed and heterogeneous pieces of evidence into a coherent reconstructed whole.

Table 2: Reconstruction models and their characteristics

| Model | Description | Strengths | Limitations |

| Potshards Model | Reconstruction from fragmented cultural or textual remains, each piece offering partial insight. | Highlights diversity of evidence; allows for multiplicity of interpretations. | Fragmentary; incomplete; may not reveal the whole picture. |

| Anastylosis Model | Reassembling ruins or texts as faithfully as possible using original elements. | Authenticity; closely preserves the form of the original. | Depends on availability of authentic fragments; risk of overinterpretation. |

| Puzzle Model | Synthesizing disparate clues into a coherent picture, even if pieces differ in origin. | Promotes creativity; integrative approach across disciplines. | Risk of forcing connections; subjective assumptions may dominate. |

3.4 Methodological Narrative Summary

In summary, the methodology proposed here offers a multi-layered approach to historical reconstruction. By weaving together semiotic decoding, linguistic analysis, and reconstruction models, the framework ensures that symbolic and textual materials are contextualized within broader cultural and archaeological settings. This approach not only identifies patterns of continuity and change but also provides a replicable model for interpreting other historical problems beyond the selected case studies.

Consilience strengthens this framework by ensuring that each interpretive step is supported by independent lines of evidence. When myths, inscriptions, artifacts, linguistic traces, and geographic markers all converge, the resulting reconstruction gains explanatory robustness that surpasses single-disciplinary approaches. Consilience thus elevates the methodology from a set of interpretive tools into a comprehensive scientific framework for historical reconstruction.

Figure 4. An intersection diagram showing total consilience of independent lines of evidence

4. Application: Case Studies

This section demonstrates the application of the proposed semiotic and linguistic framework to selected case studies. The purpose is not merely to validate historical narratives but to show how semiotic decoding, combined with linguistic analysis, can serve as a systematic tool in reconstructing the past. Each case study illustrates different levels of complexity, ranging from symbolic texts and mythical narratives to geographic identifications.

4.1 Case Study 1: Decoding Plato’s Atlantis

Plato’s dialogues in Timaeus and Critias represent a multilayered narrative in which symbols, allegories, and geographical references intertwine. Applying semiotic analysis allows us to move from the linguistic surface structure (first-order signification) to deeper cultural meanings (second-order signification). For instance, the description of concentric rings of water and land can be understood both as a literal geographical image and as a metaphor for cosmic order. By applying the puzzle reconstruction model, the fragmented clues are aligned into a plausible representation of Atlantis in the Java Sea region (Irwanto, 2015, 2016).

Figure 5. Diagram showing semiotic decoding of Plato’s Atlantis description

4.2 Case Study 2: The Land of Punt

Ancient Egyptian inscriptions and reliefs provide accounts of the Land of Punt as a divine and prosperous trading partner. Semiotic analysis of inscriptions, combined with linguistic parallels and symbolic imagery, suggests that the Land of Punt corresponds to Sumatra (Irwanto, 2015, 2019). Using the anastylosis model, fragmented references—trees, incense, animals—are reassembled to reconstruct the cultural and geographical profile of Punt.

Table 3: Summary of Egyptian Inscriptions Related to Punt

| Dynasty | Approx. Date (BCE) | Reference to Punt |

| 5th Dynasty (Sahure) | c. 2487–2475 | Reliefs show Puntite products: myrrh, incense, ebony, ivory, exotic animals. |

| 11th Dynasty (Mentuhotep III) | c. 2010 | Expedition to Punt recorded, transporting aromatic resins and exotic goods. |

| 12th Dynasty (Senusret I) | c. 1950 | Trade links with Punt mentioned, continued import of incense and luxury items. |

| 18th Dynasty (Hatshepsut) | c. 1473–1458 | Famous expedition to Punt depicted at Deir el-Bahri: incense trees, gold, animals. |

| 20th Dynasty (Ramses III) | c. 1186–1155 | Records show Puntite goods, incense, and myrrh among imported tributes. |

The inscriptions highlight the recurrent role of Punt as a source of exotic goods, sacred materials, and cultural contact between Egypt and the eastern seas. From Hatshepsut’s famous expedition at Deir el-Bahri to earlier Middle Kingdom records, Punt was depicted as a divine land of prosperity, producing incense, myrrh, ebony, ivory, gold, and exotic animals. The consistent emphasis on maritime expeditions underscores Egypt’s awareness of long-distance seafaring and the symbolic importance of Punt as both a real trading partner and a mythic “God’s Land” associated with the Sun God. Within this study, these inscriptions serve as semiotic anchors, guiding the decoding of geographic, linguistic, and cultural references that support the identification of Sumatra as the Land of Punt.

4.3 Case Study 3: Taprobana

Classical Greco-Roman sources describe Taprobana as a large island in the ‘Opposite-Earth’. The traditional identification with Sri Lanka is challenged by semiotic decoding, which emphasizes symbolic descriptions of size, wealth, and cosmological positioning. Applying the potsherds model, scattered textual fragments are assembled, indicating that Borneo better fits the ancient accounts (Irwanto, 2015, 2019). Semiotic layering demonstrates how Taprobana was a symbolic signifier of distant wealth, later misinterpreted as purely geographical.

Figure 6. Reconstructed map of Taprobana and identified geographic names

Figure 7. Map of Borneo and identified geographic names of Taprobana

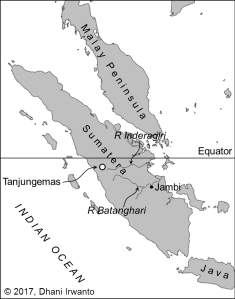

4.4 Case Study 4: Aurea Chersonesus

The Aurea Chersonesus (‘Golden Cape’) is frequently referenced in Greco-Roman sources, often associated with gold wealth, exotic products, and maritime trade networks. Traditionally identified with the Malay Peninsula, a semiotic and linguistic decoding of textual references reveals stronger alignment with its location in Sumatra at a place named Tanjungemas (‘Golden Cape’) (Irwanto, 2017, 2019). Sumatra was historically renowned for its abundant gold, spices, and strategic position in early trade routes. Applying the anastylosis model, the surviving fragments from Ptolemy, Strabo, and later travelers can be reassembled into a coherent picture of Tanjungemas as the true Aurea Chersonesus. This reinterpretation demonstrates the utility of semiotic decoding in challenging entrenched assumptions and repositioning Sumatra at the center of ancient maritime exchange.

Figure 8. Map of Sumatra showing Aurea Chersonesus (Tanjungemas)

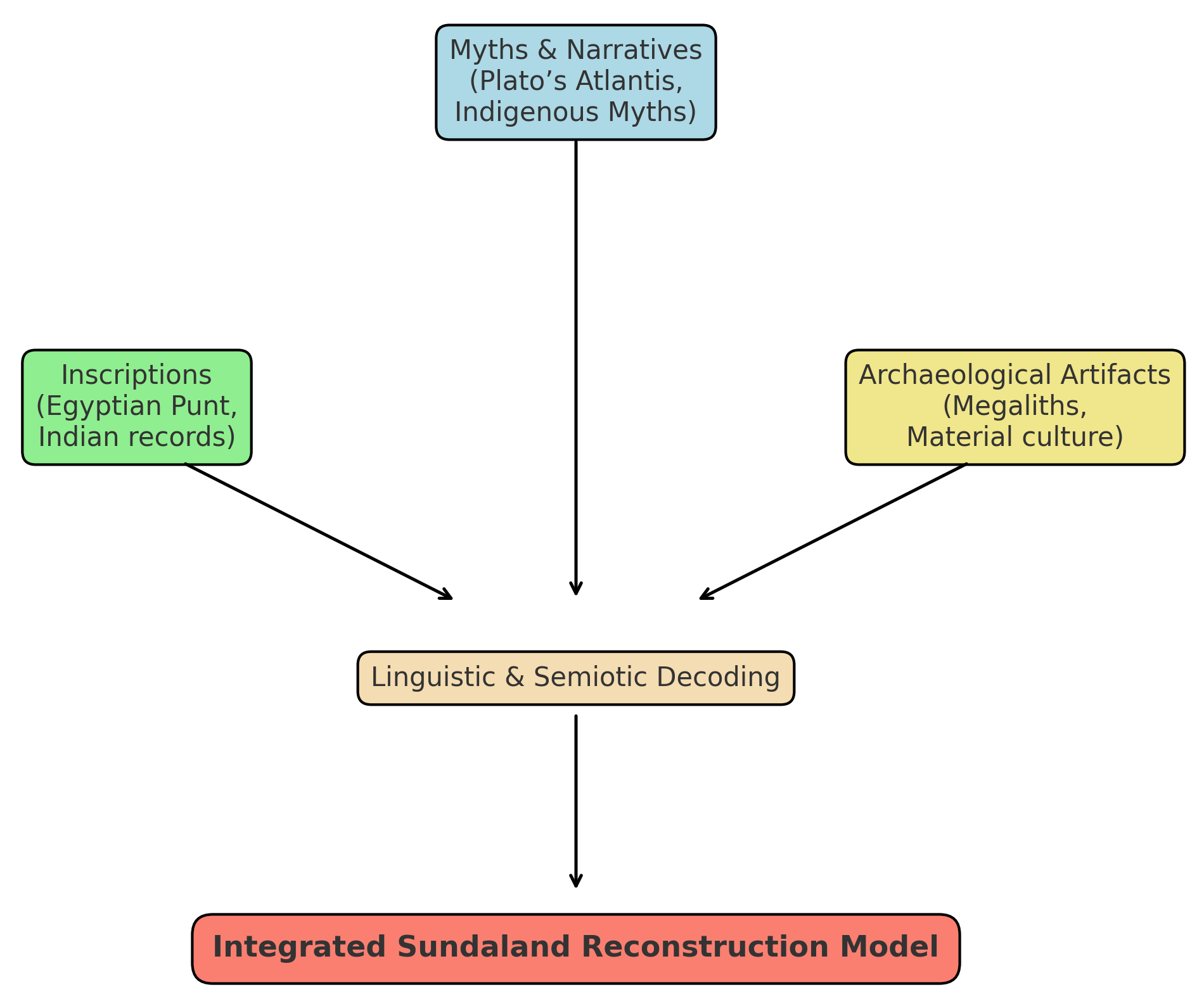

4.5 Case Study 5: Sundaland – Cradle of Civilizations

Sundaland represents a broader reconstruction where geological, archaeological, and semiotic evidence converge. Ancient myths of floods, golden lands, and lost civilizations align with the geological reality of the post-glacial sea level rise. The semiotic framework allows these disparate strands to be synthesized. By applying the puzzle and anastylosis models together, myths, inscriptions, and symbolic motifs are decoded to support Sundaland as a cradle of early civilizations (Irwanto, 2019).

Figure 9. Flowchart combining myths, inscriptions, and archaeological artifacts

into a Sundaland model

5. Discussion

The Discussion section synthesizes the methodological framework with the application of case studies, highlighting the strengths, limitations, and broader implications of semiotic and linguistic decoding in historical reconstruction. Rather than treating myths, inscriptions, or artifacts as isolated fragments, the framework unifies them into a coherent interpretive model. This discussion evaluates how well the framework performs in bridging the gap between fragmented signs and reconstructed history.

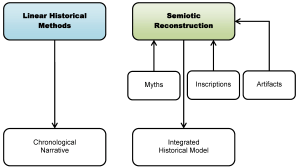

5.1 Comparative Evaluation

Comparing across the four case studies reveals both convergences and divergences in interpretive outcomes. For example, Atlantis (Plato’s narrative) and Taprobana (Greco-Roman geography) highlight how external observers encoded symbolic knowledge of distant lands, while the Land of Punt and Sundaland emphasize indigenous realities captured through inscriptions and oral memory. In all cases, the semiotic framework facilitated the decoding of signifiers beyond linguistic content—incorporating geography, material culture, and symbolic practices.

5.2 Methodological Strengths

The comprehensive framework demonstrates significant strengths:

- Flexibility in handling diverse semiotic resources (texts, inscriptions, artifacts).

- Structured analytical layers (Barthes’ orders of signification, Peircean triads).

- Practical reconstruction models (Potshards, Anastylosis, Puzzle) for fragmented evidence.

- Interdisciplinary adaptability, connecting linguistics, archaeology, and cultural studies.

- Consilience: ensures independent validation across multiple disciplines, transforming fragmentary clues into coherent and testable reconstructions. By emphasizing the convergence of evidence from myths, inscriptions, archaeology, linguistics, geography, and natural sciences, consilience strengthens the explanatory power of the framework and reduces the risks of subjectivity.

5.3 Challenges and Limitations

However, the approach faces challenges:

- Risk of interpretive subjectivity, especially in symbolic decoding.

- Fragmentary or biased historical records that resist reconstruction.

- Difficulty in achieving scholarly consensus, as debates on Atlantis or Punt illustrate.

- Limited integration with natural sciences (e.g., paleoclimate, genetics), which could further strengthen the framework.

Another significant dimension is the identification of Aurea Chersonesus, which in classical geography was often associated with the Malay Peninsula. However, based on a semiotic decoding of ancient textual and cartographic sources, this paper advances the argument that the Aurea Chersonesus was in fact located in Sumatra (Irwanto, 2017, 2019). This reinterpretation aligns with other reconstructions presented here, where linguistic traces, cultural signs, and geographic markers combine to suggest that Southeast Asia—particularly the islands of Sundaland (Irwanto, 2019)—was a nexus of ancient trade and cultural exchange. By situating Aurea Chersonesus within Sumatra, the framework challenges long-standing assumptions and strengthens the comparative coherence of the case studies, alongside Atlantis (Irwanto, 2015, 2016), the Land of Punt (Irwanto, 2015, 2019), and Taprobana (Irwanto, 2015, 2019).

5.4 Scholarly Debate

The framework situates itself within ongoing debates in historiography. Skeptics argue that interpreting myths and symbols risks producing speculative narratives, while proponents emphasize that ignoring semiotic evidence omits essential cultural knowledge. This paper positions the framework as a middle ground: rigorous enough to satisfy methodological demands while flexible enough to decode diverse forms of evidence.

Table 4. Comparative Strengths and Weaknesses of Frameworks Across Case Studies

| Framework | Strengths | Weaknesses |

| Saussurean Dyadic Model | Clarity; foundational simplicity; linguistic precision | Limited beyond language; neglects cultural context |

| Peircean Triadic Model | Flexible; accommodates cultural signs; broad analytical scope | Complexity; subjective interpretation risks |

| Barthesian Orders of Signification | Captures myth, ideology, layered meanings | Overinterpretation risk; requires careful contextualization |

Figure 10. Contrasting linear historical methods with semiotic reconstruction

6. Conclusion

This paper has proposed a comprehensive analytical framework for historical reconstruction through semiotic and linguistic decoding. By combining structural linguistics, semiotics, and reconstruction models, the framework allows researchers to navigate from fragmented symbols, texts, and artifacts toward coherent historical narratives. The strength of this methodology lies in its interdisciplinary approach, bridging linguistic analysis, symbolic interpretation, and archaeological analogy.

The application of this framework to five case studies—Atlantis in the Java Sea (Irwanto, 2015, 2016), the Land of Punt (Irwanto, 2015, 2019), Taprobana (Irwanto, 2015, 2019), Aurea Chersonesus (Irwanto, 2017, 2019), and Sundaland (Irwanto, 2019)—demonstrates its versatility. Each case highlights how semiotic decoding and linguistic reconstruction can move beyond mythic or fragmented accounts to propose plausible historical realities. These examples serve not as definitive conclusions but as illustrations of how the methodology can be applied across different cultural and temporal contexts.

A crucial pillar of this framework is the principle of consilience—the convergence of independent evidence from multiple disciplines. By ensuring that myths, inscriptions, archaeology, linguistics, geography, and natural sciences align, consilience transforms interpretive hypotheses into robust and testable reconstructions. This principle elevates the framework from an interpretive method to a comprehensive scientific approach to historical reconstruction.

Ultimately, this study contributes to the ongoing scholarly debate on the origins of civilization by shifting emphasis from singular narratives toward structured, replicable analytical methods. By treating myths, inscriptions, and symbolic records as semiotic systems open to decoding, and validating them through consilience, the framework provides a pathway for interdisciplinary collaboration and a robust tool for reconstructing human history.

7. References

7.1 Core Semiotics and Linguistics

- Barthes, R. (1964). Elements of Semiology (A. Lavers & C. Smith, Trans.). New York, NY: Hill & Wang. ISBN: 9780809080749.

- Barthes, R. (1972). Mythologies (A. Lavers, Trans.). New York, NY: Hill & Wang. ISBN: 9780374521509.

- Chandler, D. (2007). Semiotics: The Basics (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN: 9780415363754.

- Jakobson, R. (1960). Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics. In T. A. Sebeok (Ed.), Style in Language (pp. 350–377). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN: 9789997497383.

- Peirce, C. S. (1931–1958). Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (C. Hartshorne, P. Weiss & A. W. Burks, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Saussure, F. de (1916/1983). Course in General Linguistics (C. Bally & A. Sechehaye, Eds., R. Harris, Trans.). London: Duckworth. ISBN: 9780715615970.

7.2 Archaeology and Reconstruction Models

- Austin, A. (2017). Archaeological Reconstruction: Methods and Approaches. Routledge.

- UNESCO (2011). Anastylosis: Guidelines for the Reconstruction of Heritage Monuments. UNESCO Publications.

- Renfrew, C., & Bahn, P. (2016). Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice (7th ed.). London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN: 9780500292105.

- Whewell, W. (1840). The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences. London: John W. Parker.

- Wilson, E. O. (1998). Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. New York: Knopf. ISBN: 9780679450771

7.3 Classical and Historical Sources

- de Sélincourt, A. (Trans.). (1996). Herodotus: The Histories. London: Penguin Classics.

- Jones, H. L. (Trans.). (1932). Strabo: The Geography. Harvard University Press.

- Waterfield, R. (Trans.). (2008). Plato: Timaeus and Critias. Oxford University Press.

- Jones, H. L. (Trans.). (1924). The Geography of Strabo. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Berggren, J. L., & Jones, A. (Trans.). (2000). Ptolemy’s Geography: An Annotated Translation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Duemichen. J. (1869). Historiche Inschriften Altägyptischer Denkmäler. Leipzig.

- Mariette-Bey. A. (1877). Deir-El-Bahari, Documents Topographiques, Historiques et Ethnographiques, Recueillis dans Ce Temple. Leipzig JC Hinrichs.

- Edwards. A. A. B. (1891). Pharaohs Fellahs and Explorers, Chapter 8: Queen Hatasu, and Her Expedition to the Land of Punt (pp 261-300). New York: Harper & Brothers.

7.4 Case Studies and Regional Applications

- Irwanto, D. (2015). Atlantis: The Lost City is in the Java Sea. Bogor: Indonesia Hydro Media. ISBN: 9786027244917.

- Irwanto, D. (2016). Atlantis: Kota yang Hilang Ada di Laut Jawa. Bogor: Indonesia Hydro Media. ISBN: 9786027244900.

- Irwanto, D. (2019). The Land of Punt: In Search of the Divine Land of the Egyptians. Bogor: Indonesia Hydro Media. ISBN: 9786027244948.

- Irwanto, D. (2019). Taprobana: Classical Knowledge of an Island in the Opposite-Earth. Bogor: Indonesia Hydro Media. ISBN: 9786027244962.

- Irwanto, D. (2019). Sundaland: Tracing the Cradle of Civilizations. Bogor: Indonesia Hydro Media. ISBN: 9786027244924. (includes section on Aurea Chersonesus)

- Irwanto, D. (2015). The Land of Punt is Sumatera. AtlantisJavaSea.com. Retrieved from https://atlantisjavasea.com/2015/11/14/land-of-punt-is-sumatera/

- Irwanto, D. (2015). Taprobana is not Sri Lanka nor Sumatera, but Kalimantan. AtlantisJavaSea.com. Retrieved from https://atlantisjavasea.com/2015/09/26/ taprobana-is-not-sri-lanka-nor-sumatera-but-kalimantan/

- Irwanto, D. (2017). Aurea Chersonesus is in Sumatra. AtlantisJavaSea.com. Retrieved from https://atlantisjavasea.com/2017/06/08/aurea-chersonesus-is-in-sumatera/